I did it: I read everything published by Epic Comics.

Was that a good idea? No.

Did Epic publish good comics? Well… They published some extraordinary books, but there were a whole bunch of duds.

Below is an overview of all the comics, with links to the individual blog articles. I’ve split Epic’s history into broad sections, because Epic’s publishing strategy changed several times over the years. These aren’t hard and fast categories, because previous publishing initiatives (mostly) continued running while Epic changed direction.

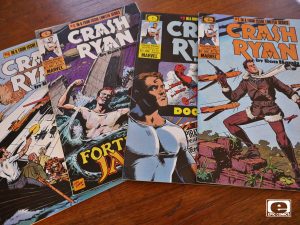

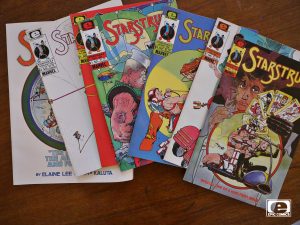

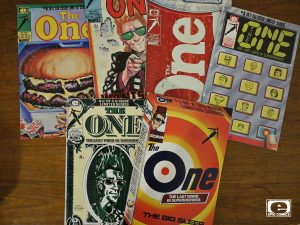

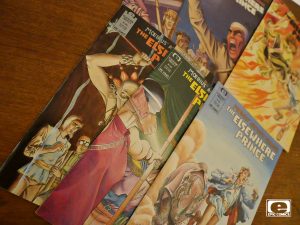

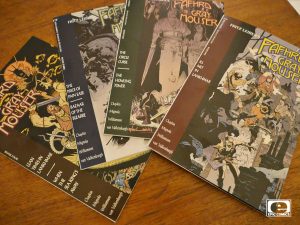

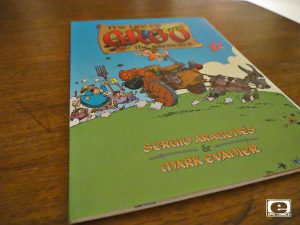

Phase One: Lure creators away from Eclipse

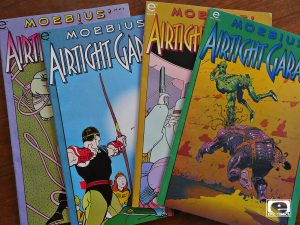

The more or less stated reason for Marvel starting the Epic initiative was to lure creators that had defected from Marvel back to the fold. The people left for two reasons: 1) They wanted to own their own work, and 2) they had major problems with the editors that worked at Marvel; Jim Shooter in particular.

With Epic, creators would own their own work, and while Shooter was still editor-in-chief at Marvel, Archie Goodwin, a well-liked veteran editor, was supposed to be the firewall between the creators and Marvel proper.

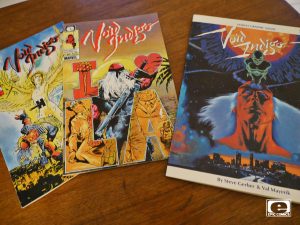

This worked out in the beginning, but it didn’t really last: Shooter summarily cancelled Steve Gerber and Val Mayerik’s Void Indigo after just two issues after complaints about the excessive violence in that book.

The creator ownership bit did work… but the way artists (in particular) were shifted around on the books, it did start to look more like Marvel in general. There were train wrecks like the Video Jack series where the principal creators seemed to lose interest after an issue or two, and even on high-profile series like Moonshadow, the artist left the book and had to be replaced on the final three issues.

That sort of stuff is less than ideal, and derailed a good number of the initial batch of Epic books. Oddly enough, it (mostly) stopped happening after Archie Goodwin left Epic, so I don’t know what that means.

In one instance, the associate editor of a series (Timespirits) was fired for siding with the artist against Goodwin’s wishes, apparently.

But the main problem for Marvel with all of this was… that these comics didn’t really sell much. In the initial euphoria of the direct sales market (i.e., 80-83), publishers like Eclipse and Pacific published a large number of quirky titles that were snapped up by the market, but after a while the readers seemed to decide that they were fine with just reading super-hero books, thank you very much. So Epic was launched too late to do much business, which left Marvel looking for new things to do with the imprint.

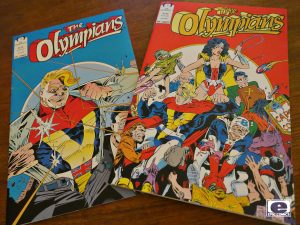

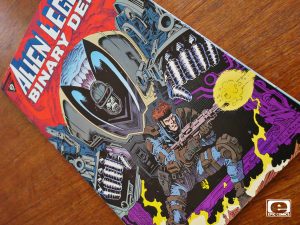

Phase Two: Perhaps super-heroes aren’t so bad after all

Archie Goodwin stated that he had no interest in doing super-hero books, and it would be unlikely that Epic would publish them.

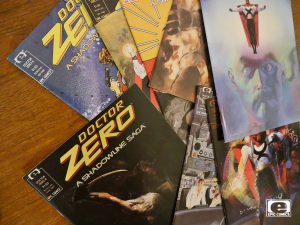

After Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, but particularly after Marvel told him to, he changed his mind and developed a super-hero universe for Epic: The Shadowline saga. Three continuing series resulted (and a crossover series), but they weren’t successful, either commercially or critically.

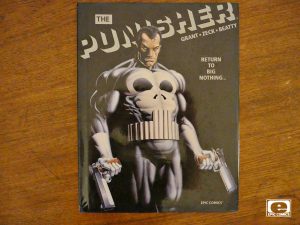

Another tack taken around this time was to just do more “upscale” versions of the Marvel characters, which resulted in stuff like the Havok/Wolverine series Meltdown. This was apparently not very successful, either, because the fans didn’t consider these part of the “real” continuity.

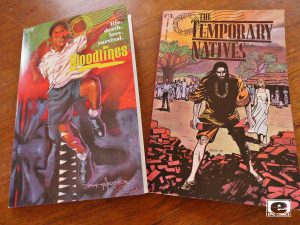

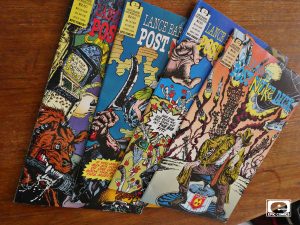

Phase Three: Let’s be adult

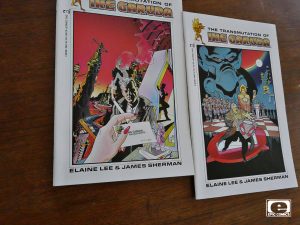

Doing super-heroes under the Epic label made little sense: They’d sell better at Marvel proper, so how about returning slightly to the original concept: Just creator-owned comics, but now published as stand-alone albums and “prestige format” mini-series?

Archie Goodwin left Epic in 1989 (for DC Comics), and Carl Potts took over the reins. You can see the differences pretty clearly — for instance, somebody at Epic had a mania for doing in-story plot recaps, so almost every issue in the Goodwin-edited era spent a few pages with people going “as you know, Robert, I am your brother and we are building a space ship”. This ended when Goodwin left, fortunately, so I’m guessing he had something to do with it.

The other thing was that Epic published mostly bi-monthly series, and if the artists were late, Epic would often hire new artists to fill in (usually to the disappointment of this reader). The new publishing methodology appeared to be to have a bunch of issues in-house before starting to publish, and then publish everything on a monthly schedule. No creative substitutions, few delays.

Both of these changes make for better comics.

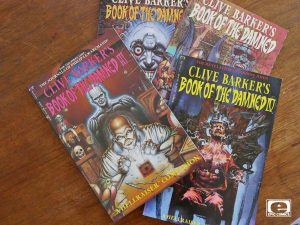

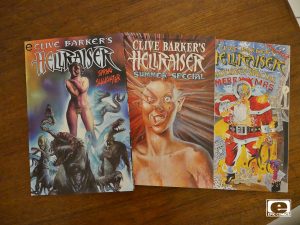

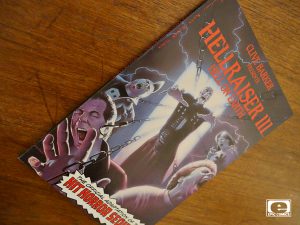

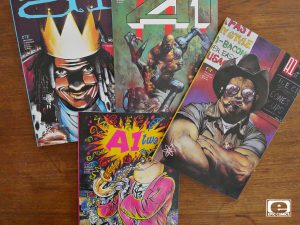

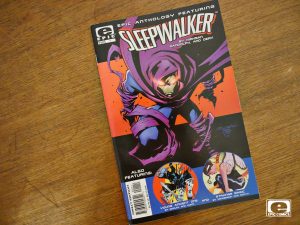

But there’s two other strains of comics in this phase: 1) Clive Barker spin-offs and 2) comics coming out of Marvel UK, but published under the Epic banner.

Neither of these result in any comics that are actually, like, good (except the A1 anthology). And some of them are the worst that Epic ever published.

So it’s a mixed era.

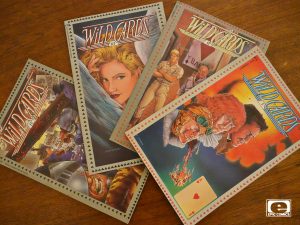

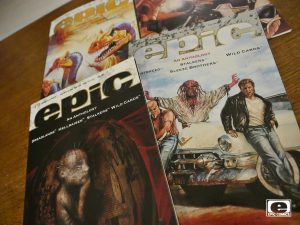

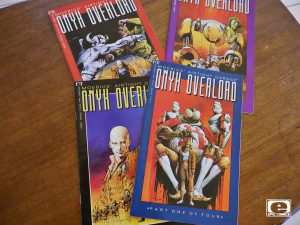

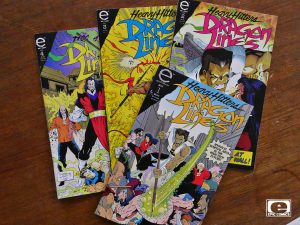

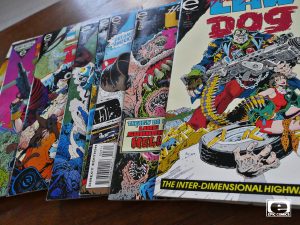

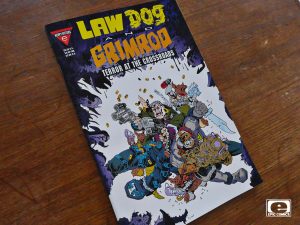

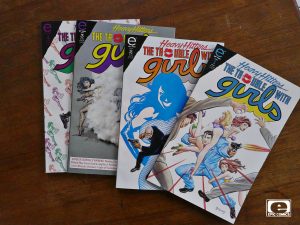

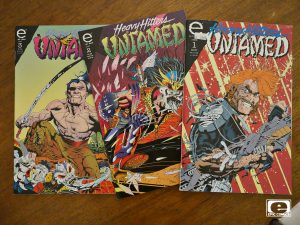

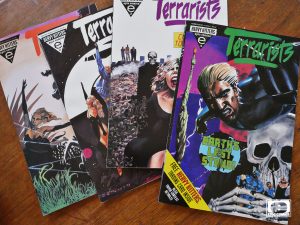

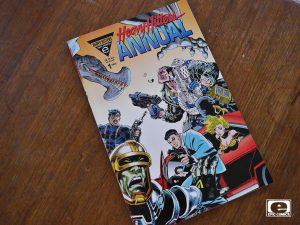

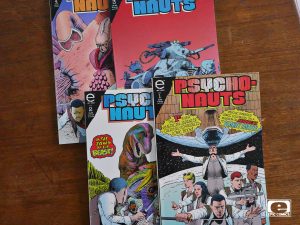

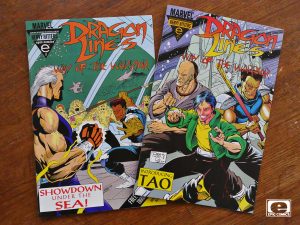

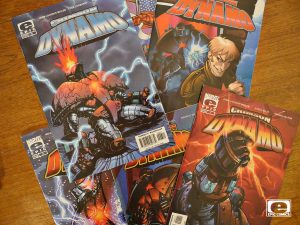

Phase Four: Heavy Hitters

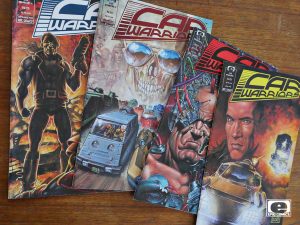

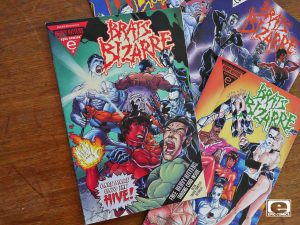

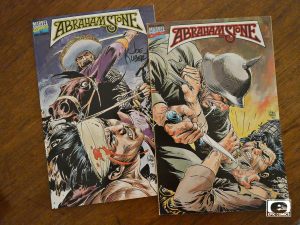

All the fan favourite artists left Marvel over the previous years, and the industry was now dominated by Image Comics. Marvel’s sales were in the toilet, so they made a cunning plan to fight this by just flooding the market with new titles, including new-look Epic Comics. They made a new, “edgier” logo, and hired a bunch of bigger creators to create some buzz.

So to fight Jim Lee, they launched stuff like… Joe Kubert’s Tor.

To the apparent surprise of Marvel and nobody else, none of these comics sold anything. (If I’m reading the interwebs correctly.)

So Marvel finally shut Epic down, and a couple years later, went into bankruptcy.

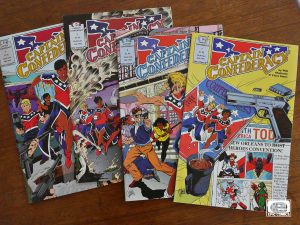

Ironically enough, I think that this phase is one of Epic’s most successful, artistically. (Don’t you think?) That is, more than half of these comics are, like, you know, interesting: They’re more like what Epic was envisioned being than at any previous time in its history. They’re usually created by a single creator and they’re quirky as hell.

But this was definitely not the time to launch books that read like throwbacks to the direct sales market of 1984.

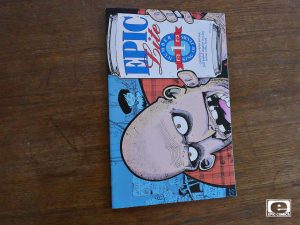

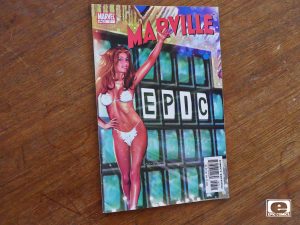

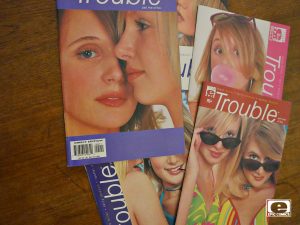

Phase Five: Catfishing fans

In 2003, then-president Bill Jemas came up with the brilliant idea to have fans pitch unusual takes on Marvel characters (and perhaps newly-created concepts), and Marvel would then publish these under the Epic banner, so that readers wouldn’t get all confused. Marvel promised to have minimal editorial involvement, so they’d basically just print whatever whacky thing they’d be getting.

It’s a win-win: Marvel would get new talent, and Marvel wouldn’t have to spend any money on that talent. (Win-win for Marvel, of course — the creators wouldn’t own the work.)

At least that’s what reading Marville #7 makes it sound like.

In reality, the creators make it sound like they went through a nightmarish editorial gauntlet to get their stuff into publishable form, and the flood of submissions was a huge time sink for Marvel.

Jemas was fired, Epic was shut down. Again.

I think you add links to your other blogs/sites on this site’s sidebar. It’d be really convenient.

Good idea. Now added.

I’d really love to know what your favorites were in all this (without having to read every individual entry). You read all those bad books so we don’t have to! What a service to humanity. So tell us, what were the masterpieces, the must-reads, the biggest surprises, the most idiosyncratic, the hidden gems…?

Pingback: reddit.com