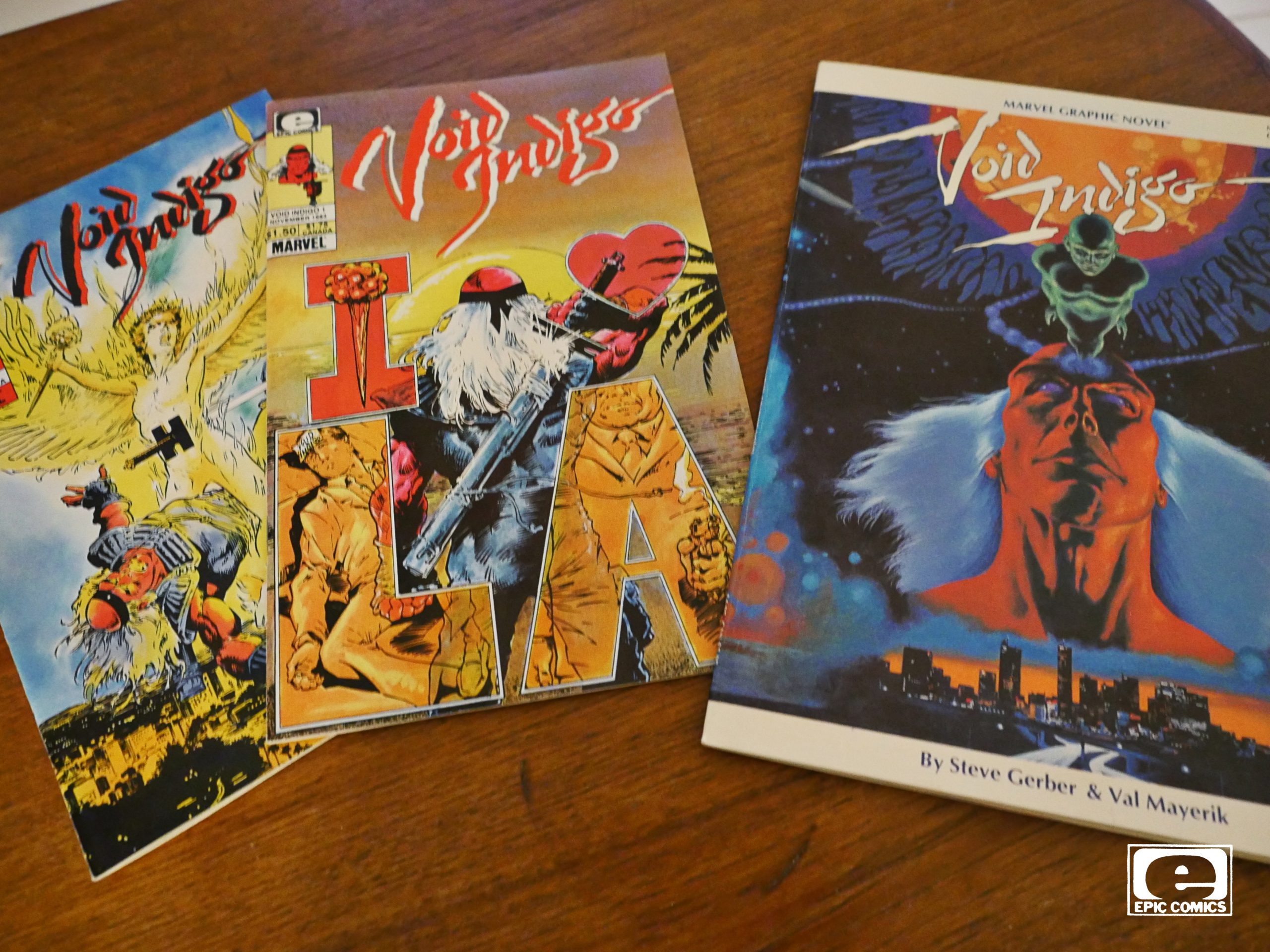

Void Indigo (1984) #1-2

by Steve Gerber and Val Mayerik

Ah, the infamous Void Indigo: I remember it being a much talked-about comic at the time… because it was cancelled for being too violent. I think.

I had these issues as a teenager, and I was not a fan. I was rather squicked by it all.

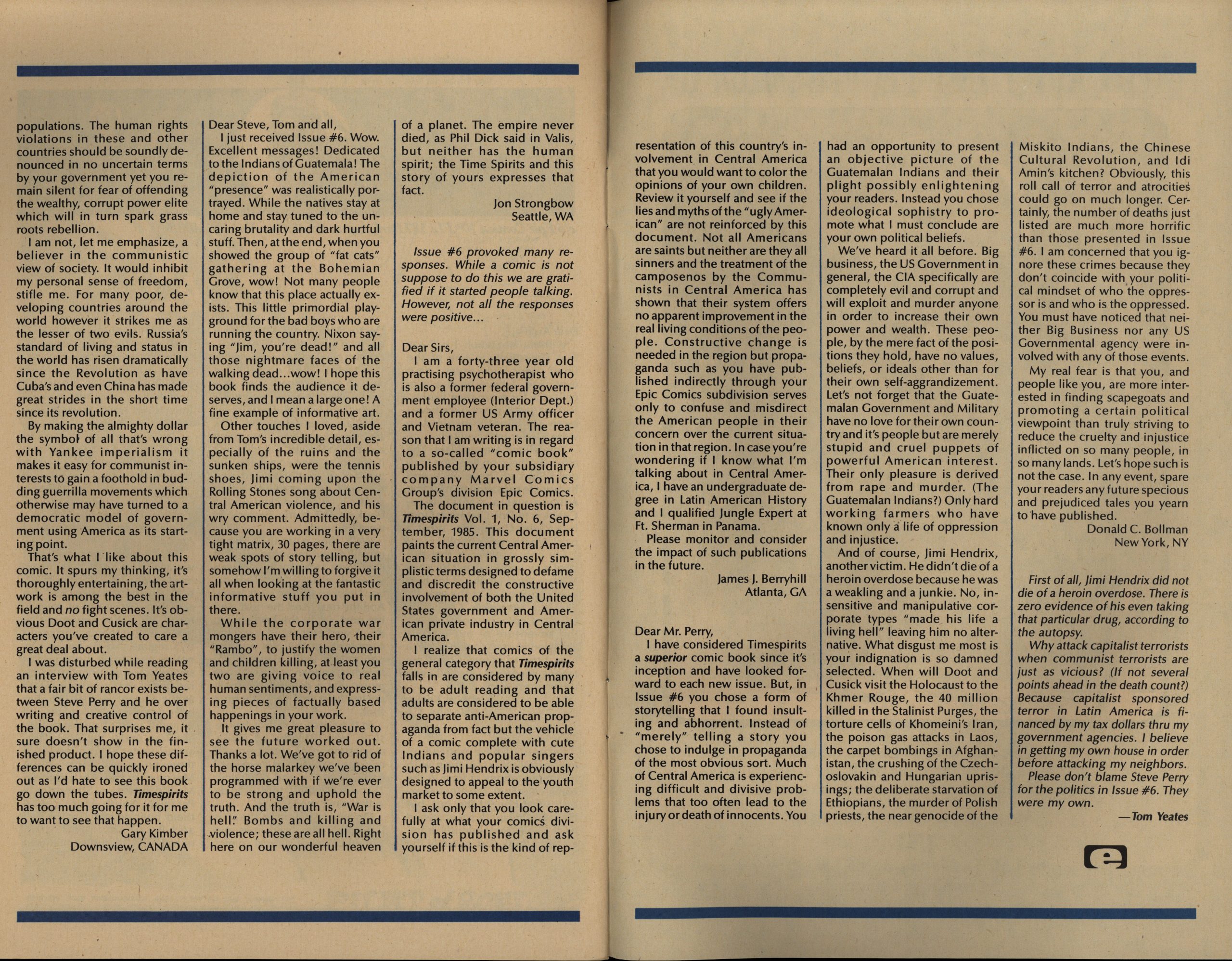

Steve Gerber famously left Marvel in the late 70s, and sued them for ownership of the Howard the Duck character, so there was a lot of bad blood between them. But Epic Comics was formed as a way to lure writers such as Gerber back into the fold, with Archie Goodwin supposedly forming a firewall between the creators and the other Marvel people (especially Jim Shooter, who many felt were responsible for their miserable Marvel experience).

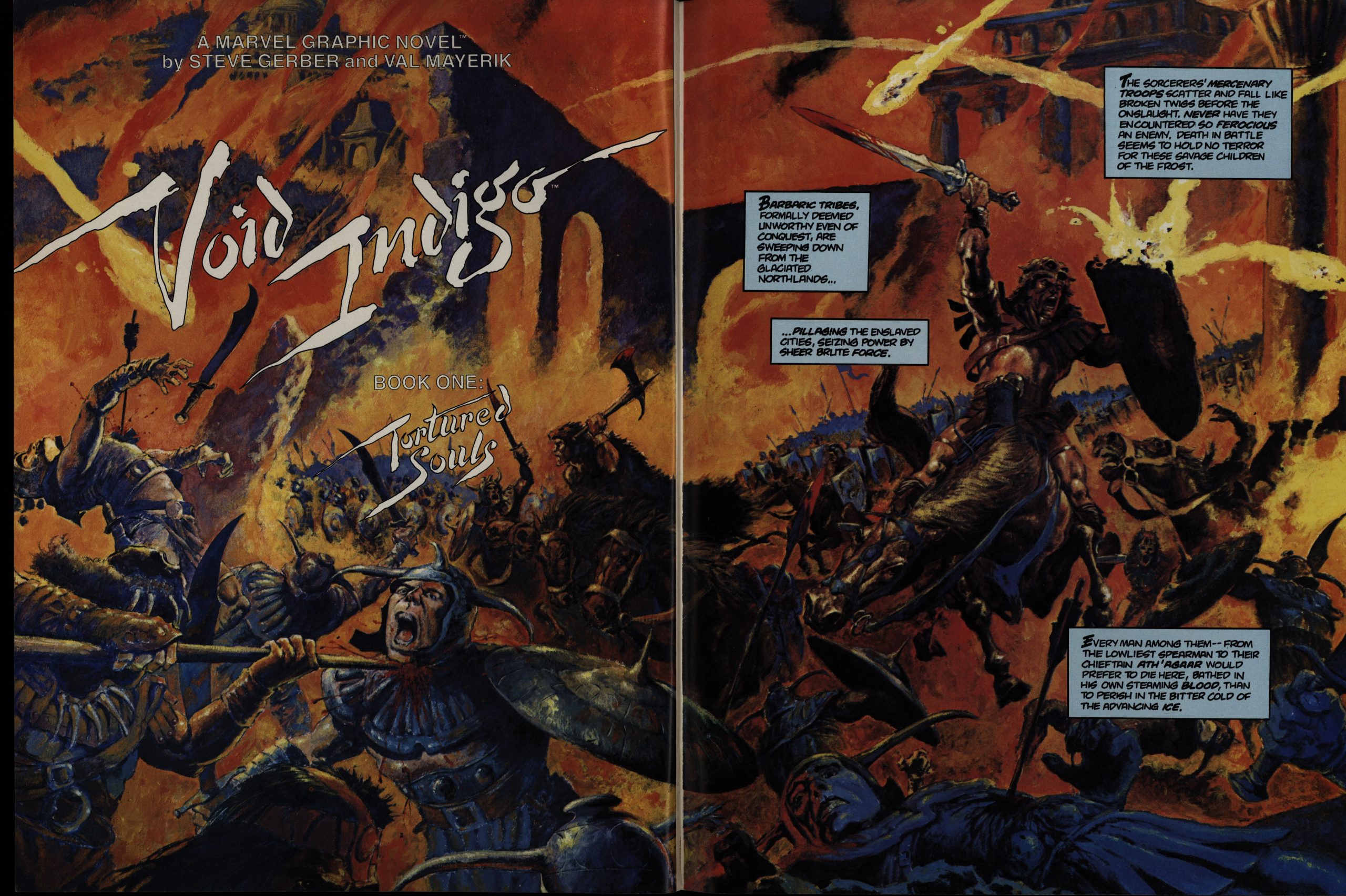

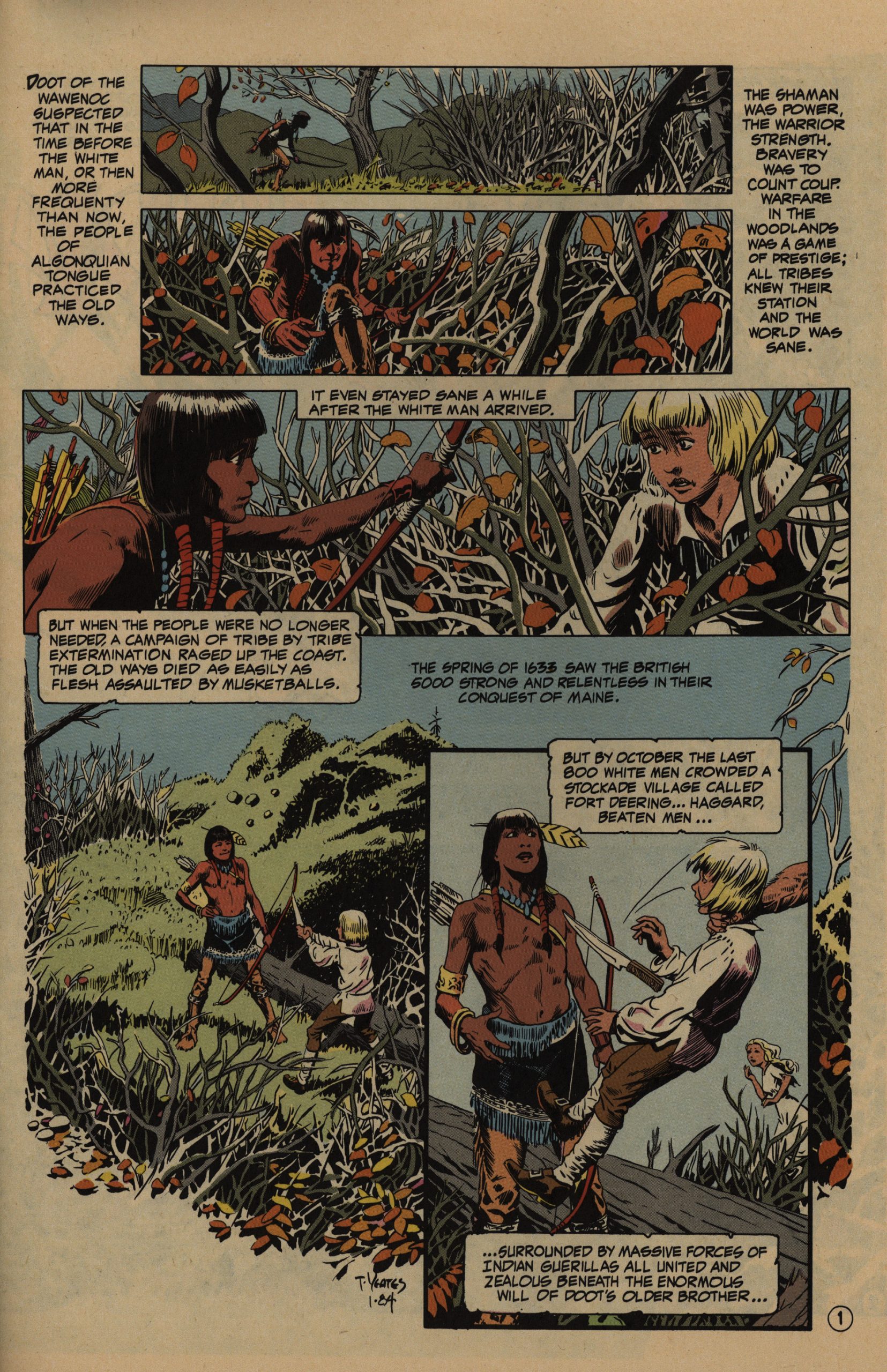

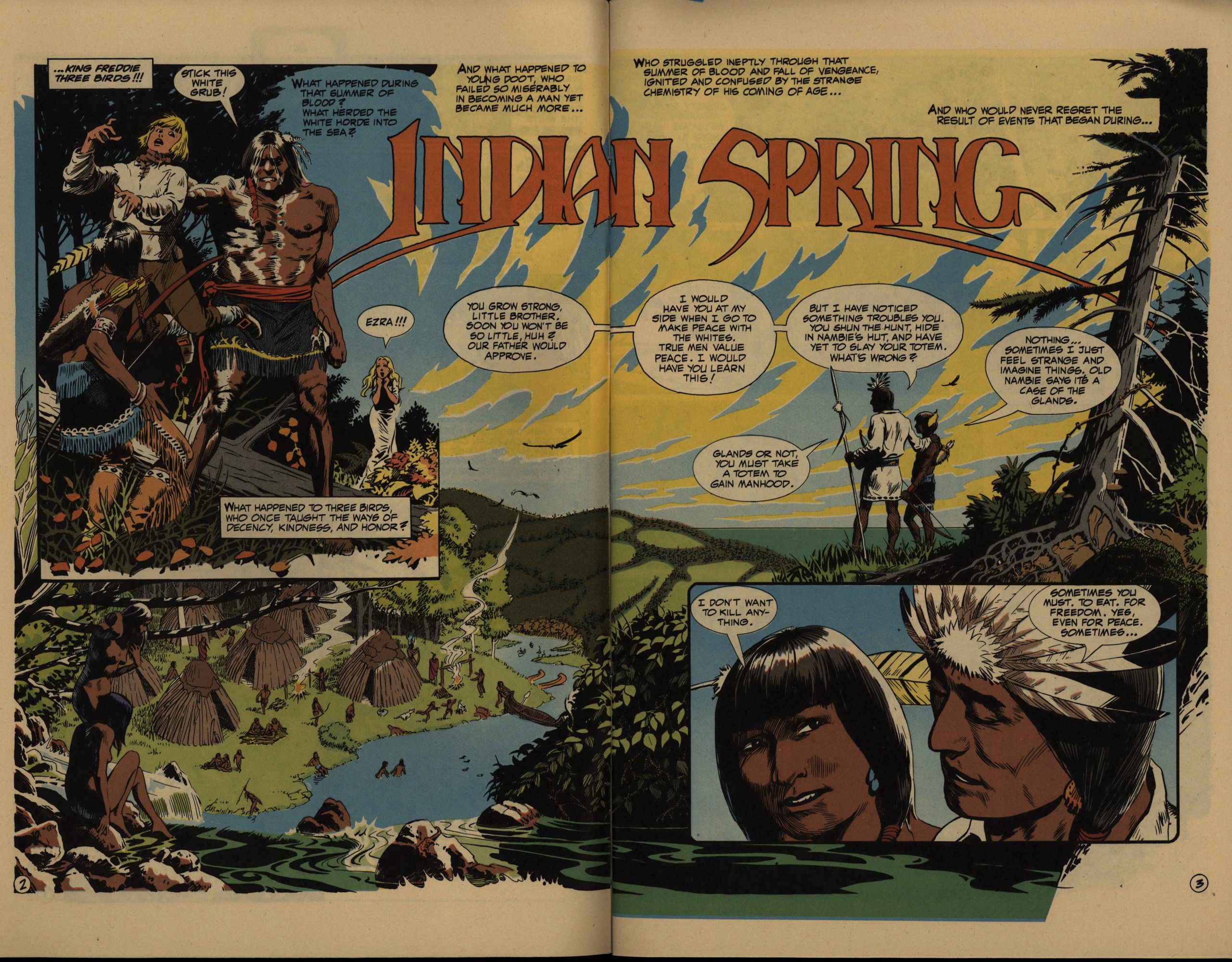

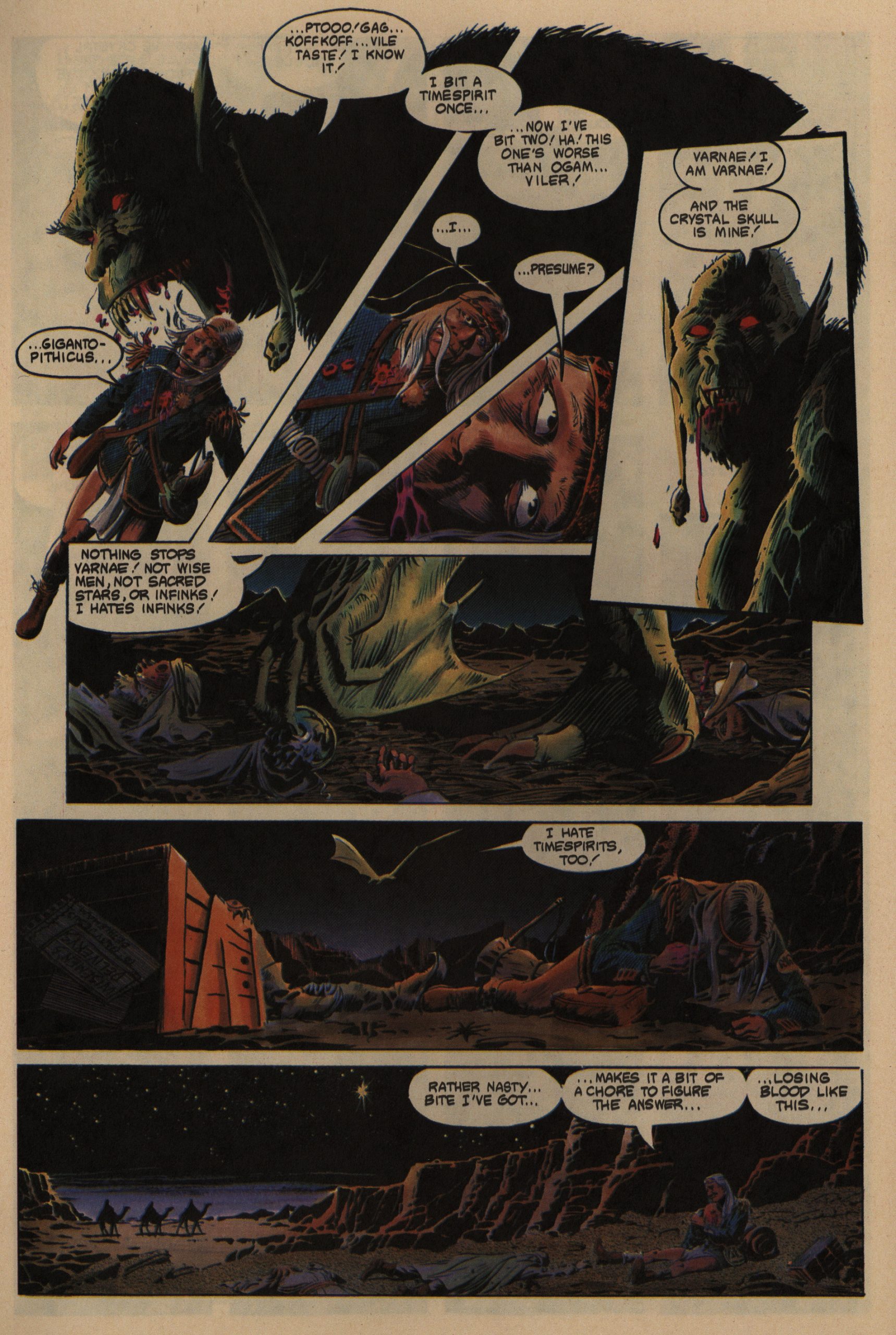

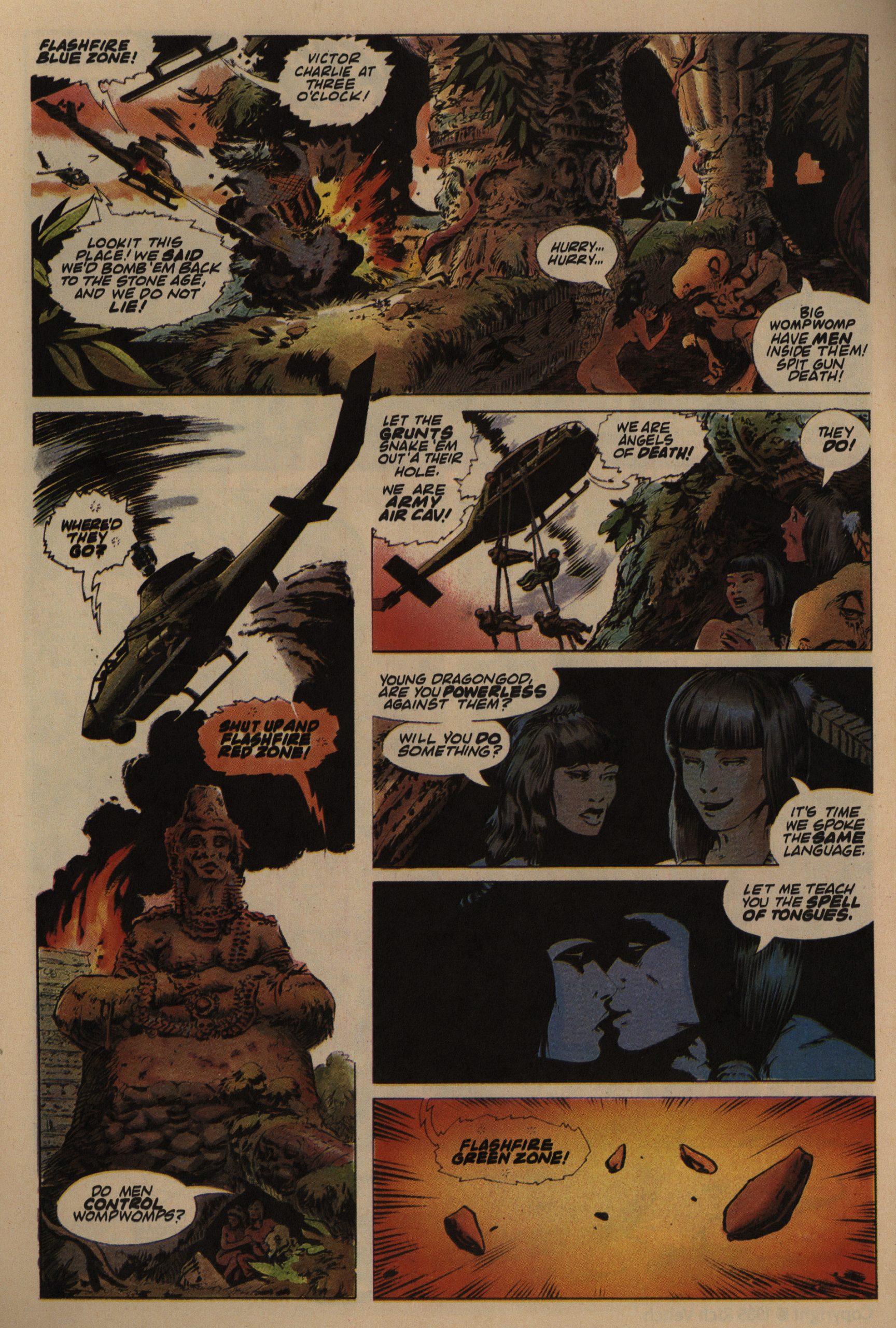

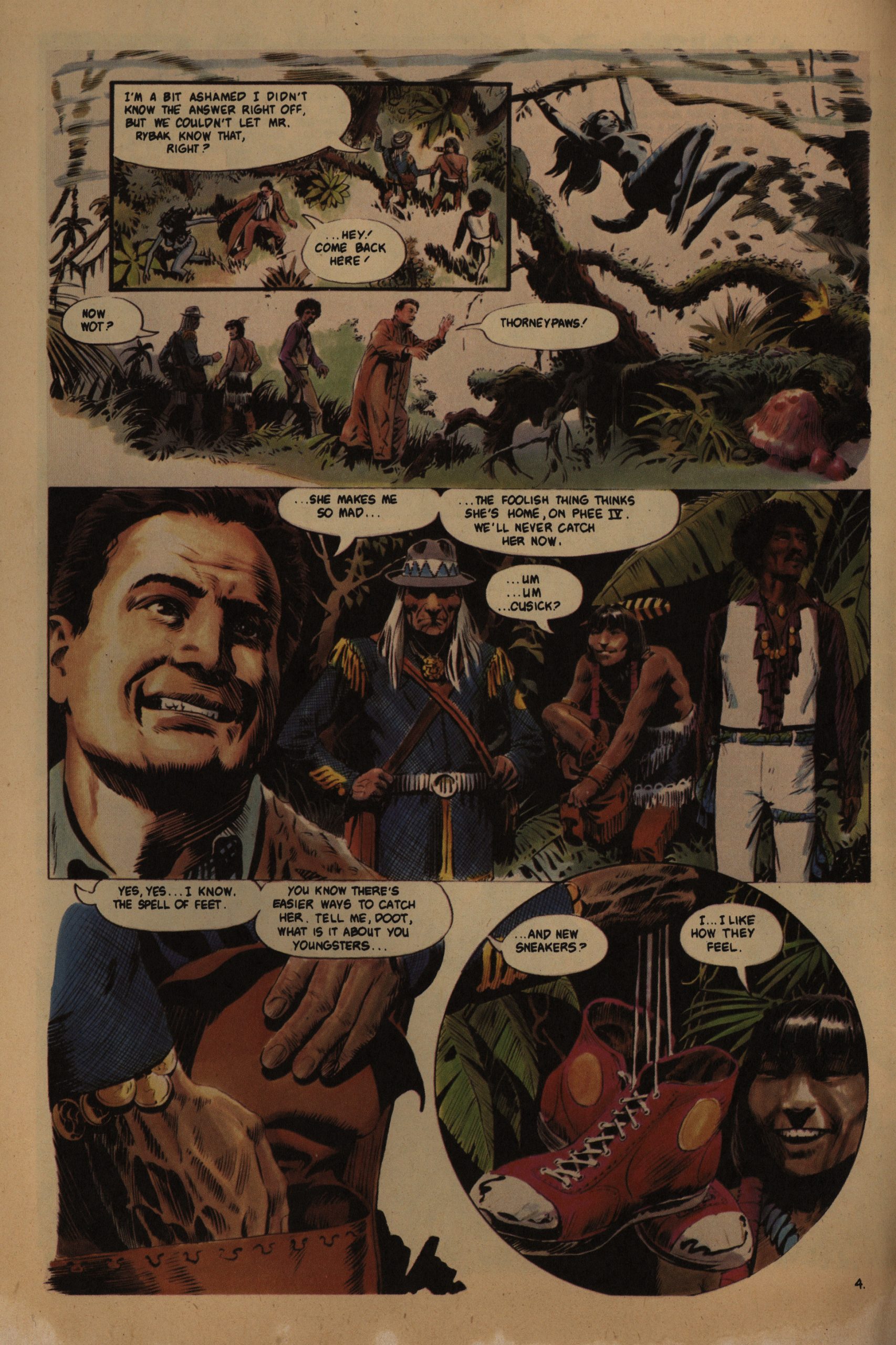

Before the Epic Comics series, Marvel published a Void Indigo graphic novel. In retrospect, it’s a weird way of introducing a series, but back in the mid 80s, companies were trying out a bunch of different publishing models. Gerber and Mayerik certainly make their intentions known from the start: We open with a fully-painted spread of violence and mayhem.

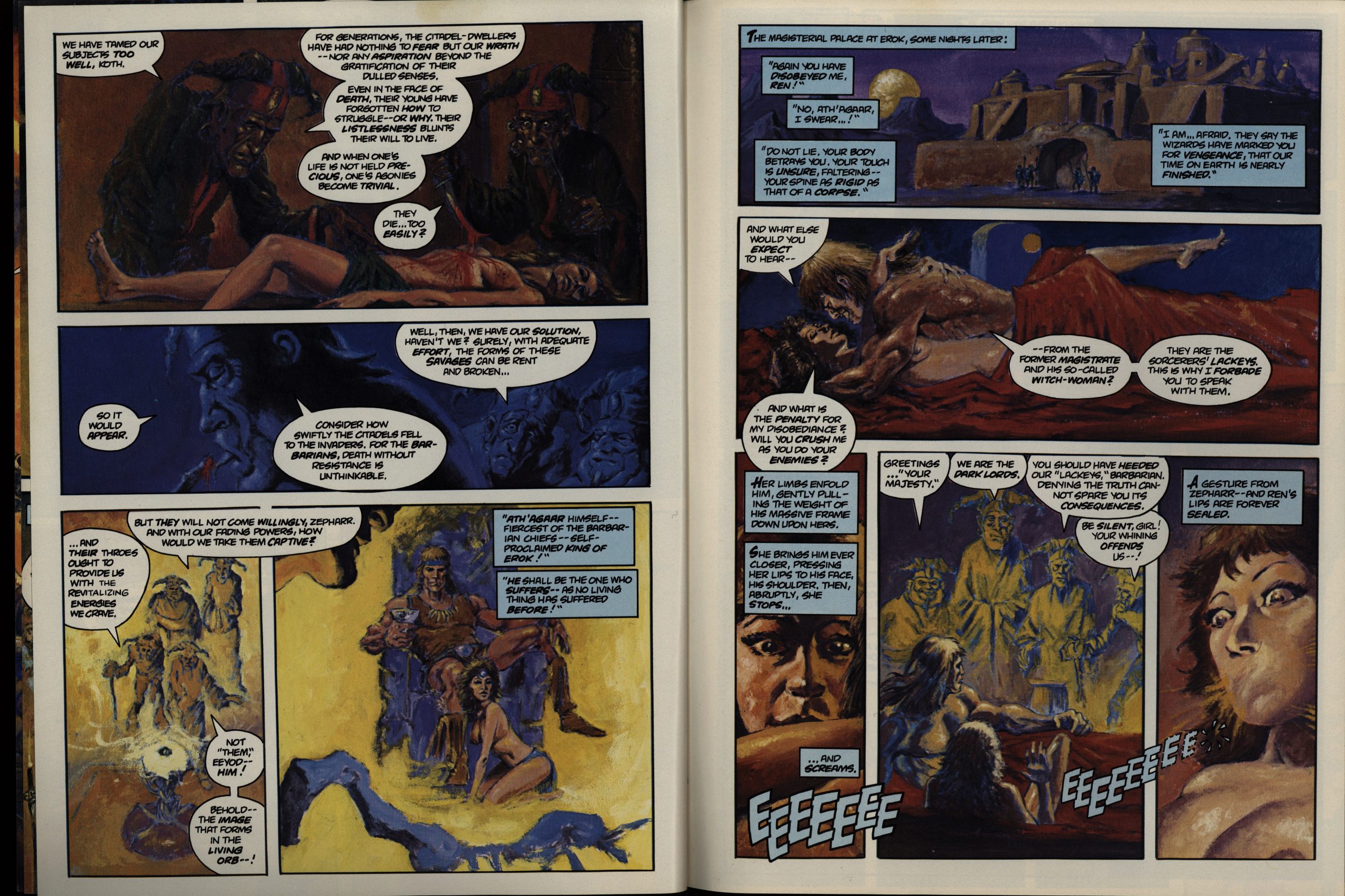

Oh, that scene I still remembered from when I last read this over 30 years ago. (And the torture starts on the next page, but I’ll spare you that: It’s vile.) There’s something about mouths disappearing that’s particularly nauseating to me.

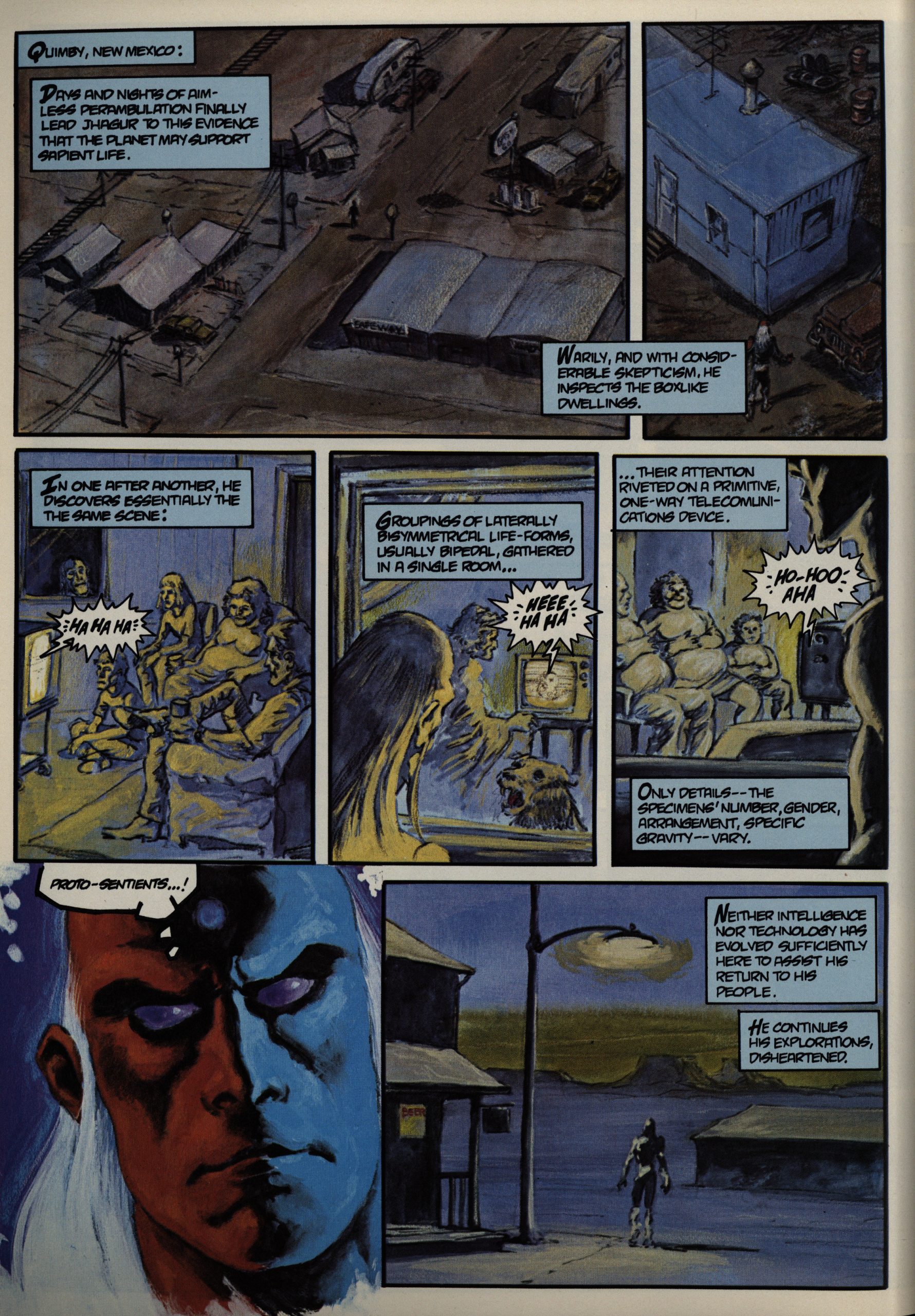

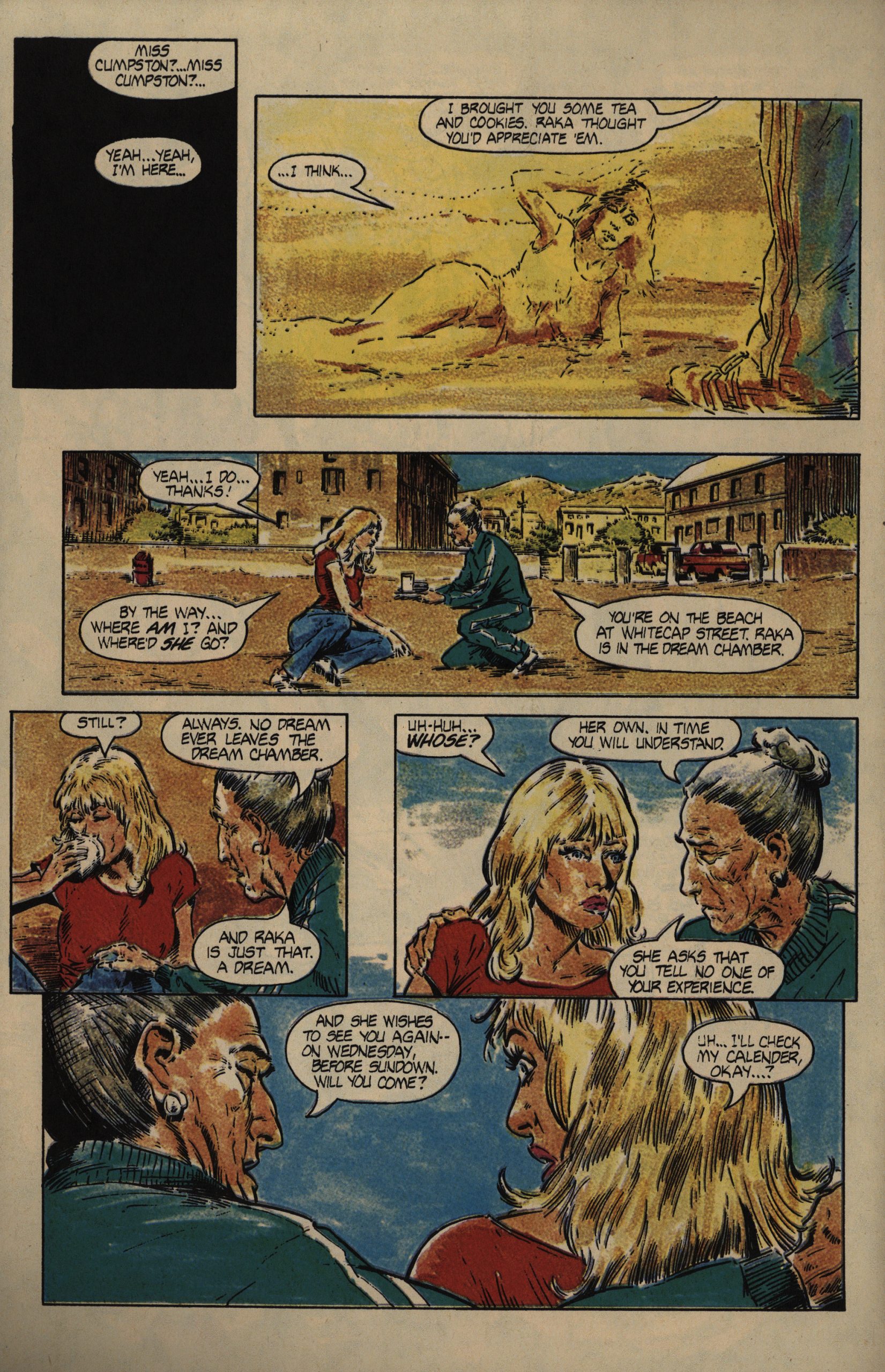

The murder and torture is just the preamble, though: Then we go to Earth and our protagonist meets use proto-sentients.

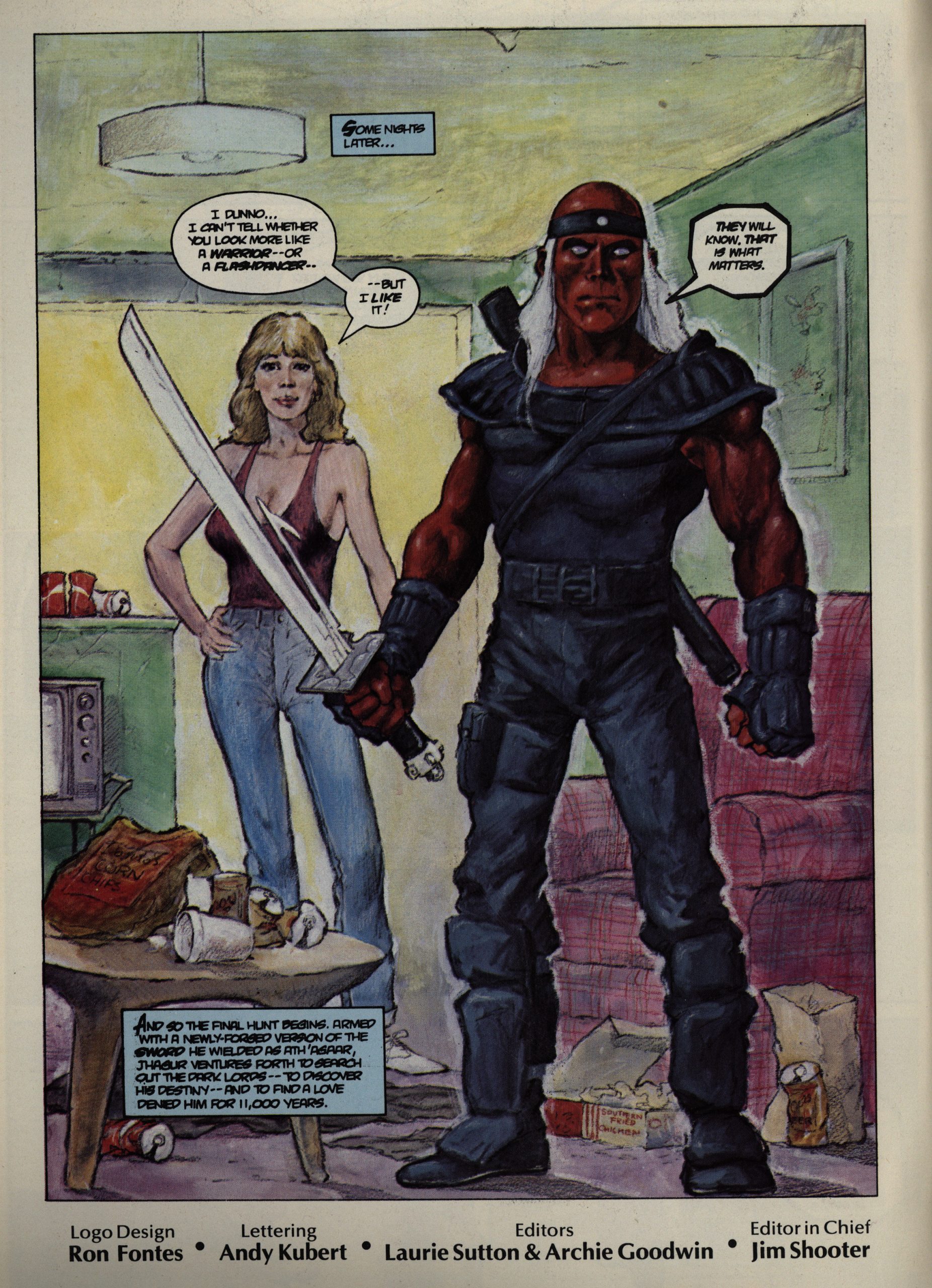

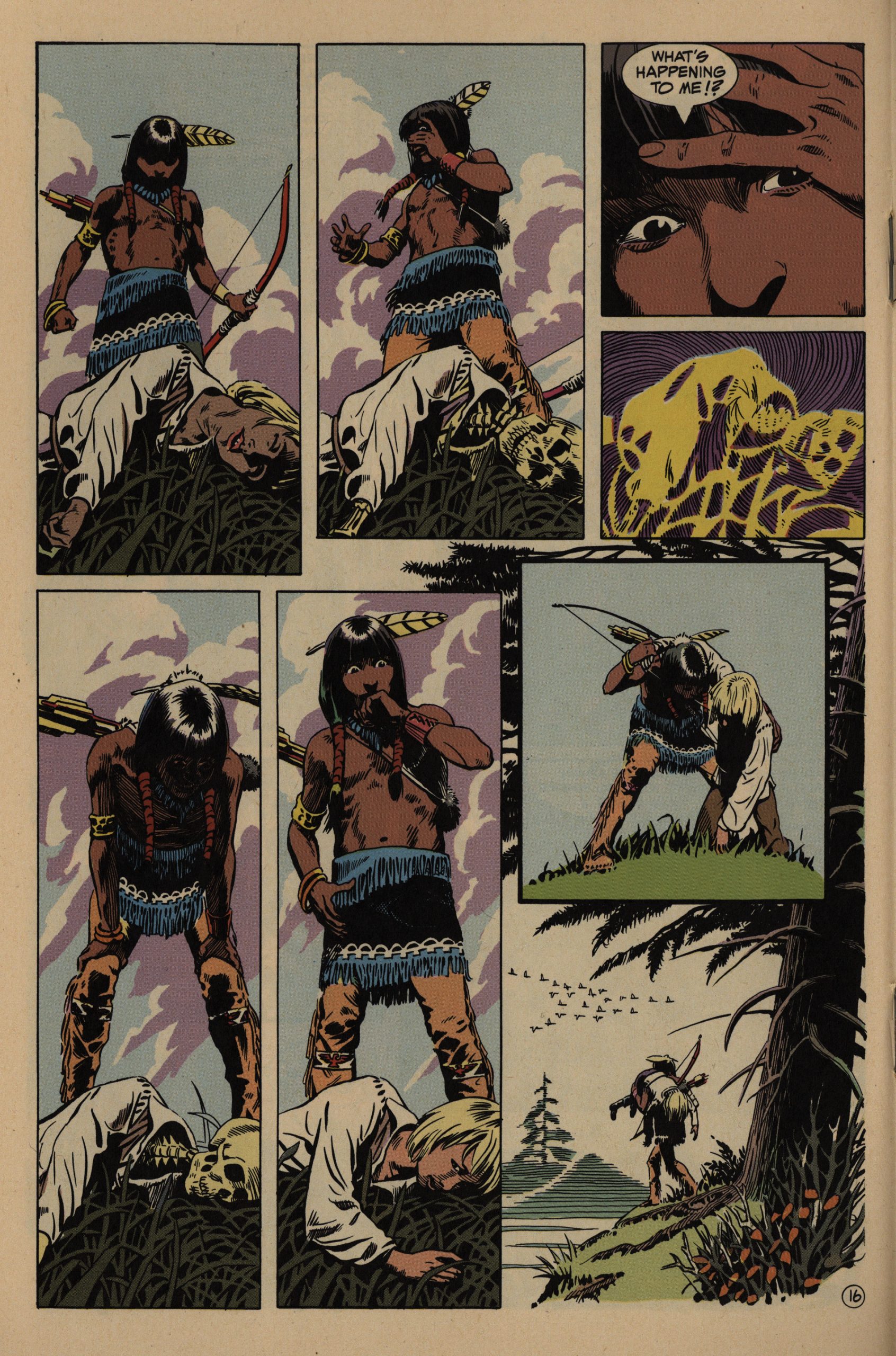

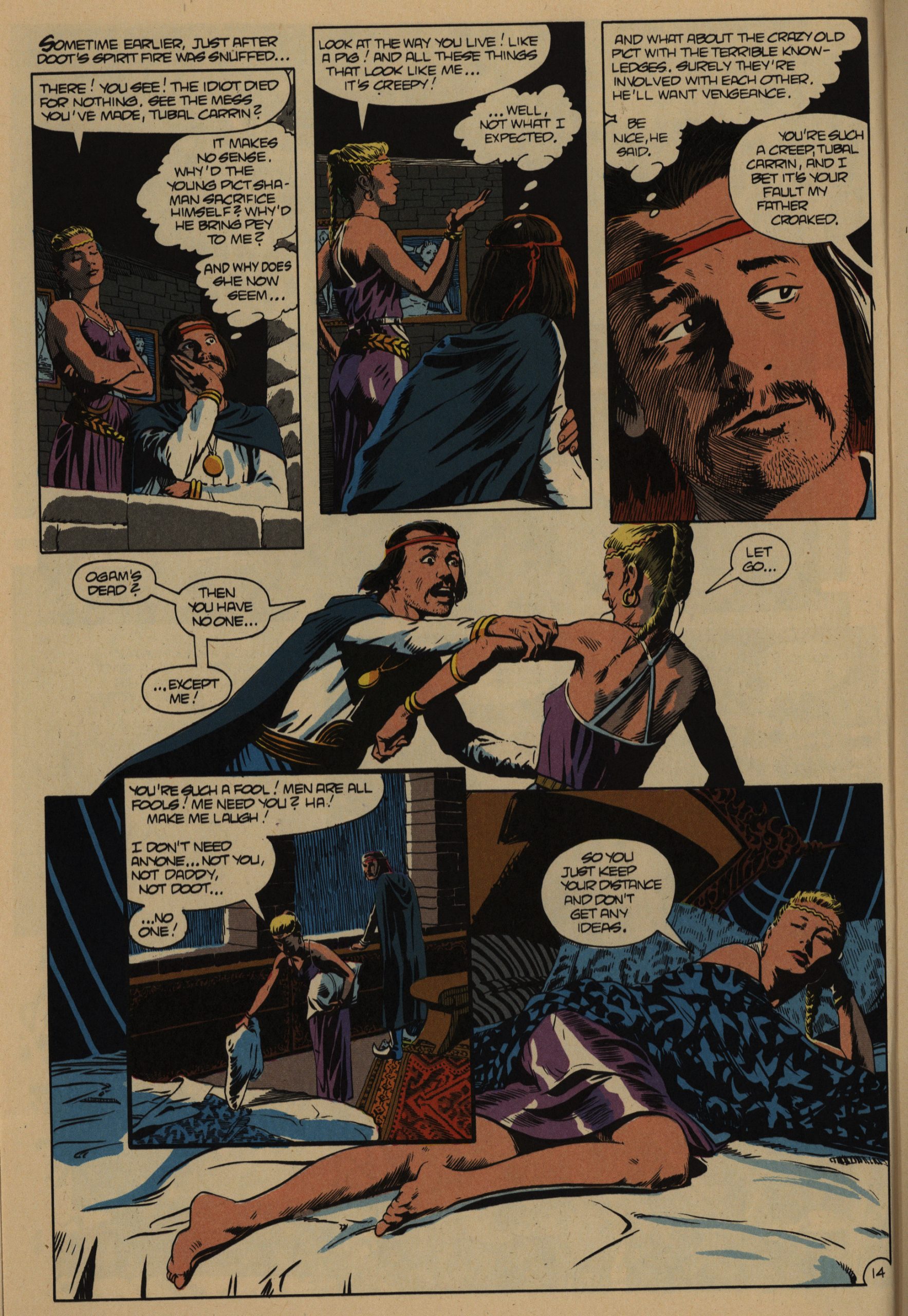

As a graphic novel, it’s… not. It reads like what it is: A superfluous barbarian super-hero origin preamble. Nothing much interesting happens in it, and it’s practically devoid of structure. It’s by no means a satisfying reading experience, and Mayerik’s painted artwork isn’t as accomplished as his pencil-and-ink artwork. He’s always had a problem with human proportions, and head size/body size proportions are perpetually off and fluctuating.

So that’s not an auspicious introduction to Void Indigo… especially as it doesn’t really seem to be necessary for the series that follows, either.

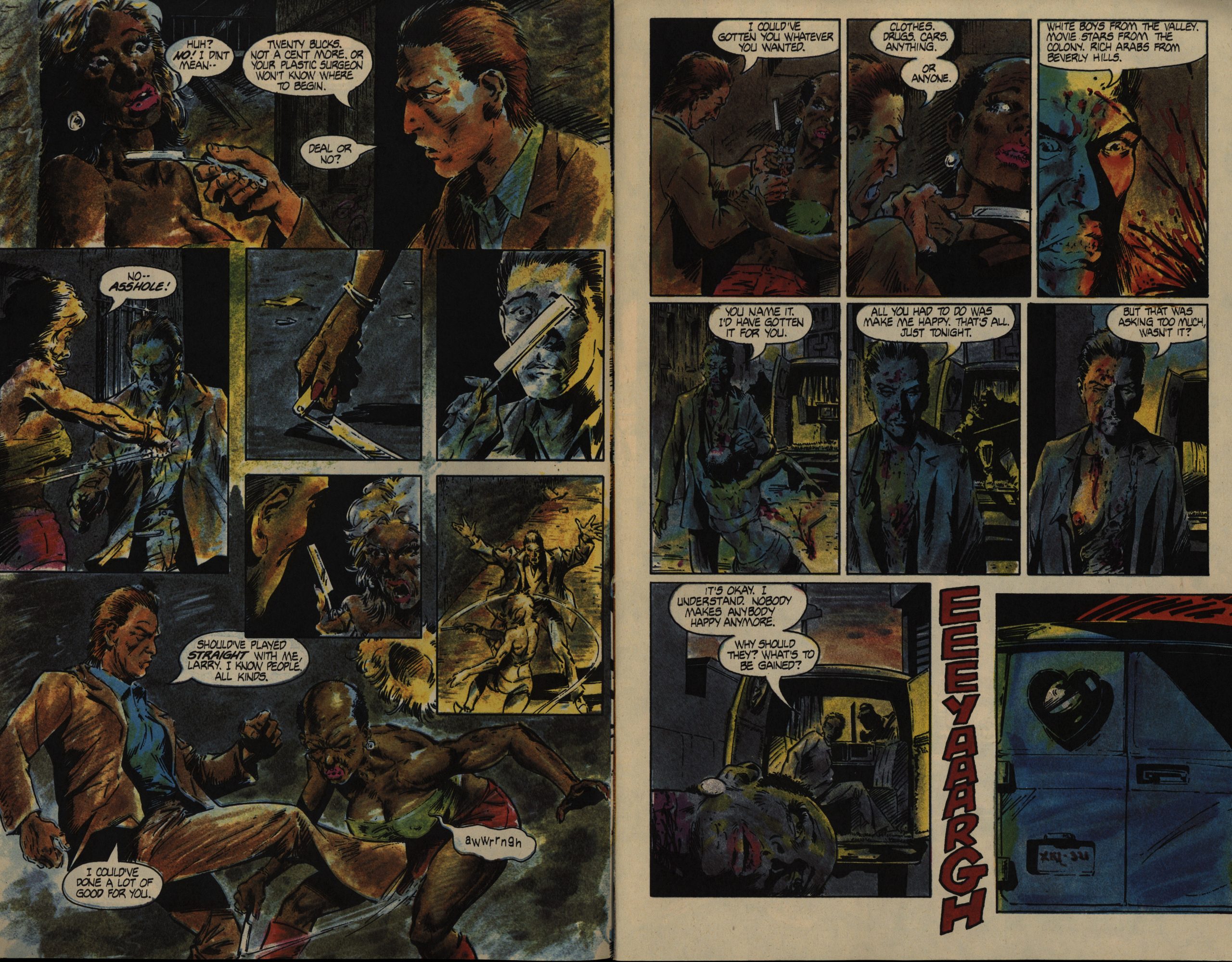

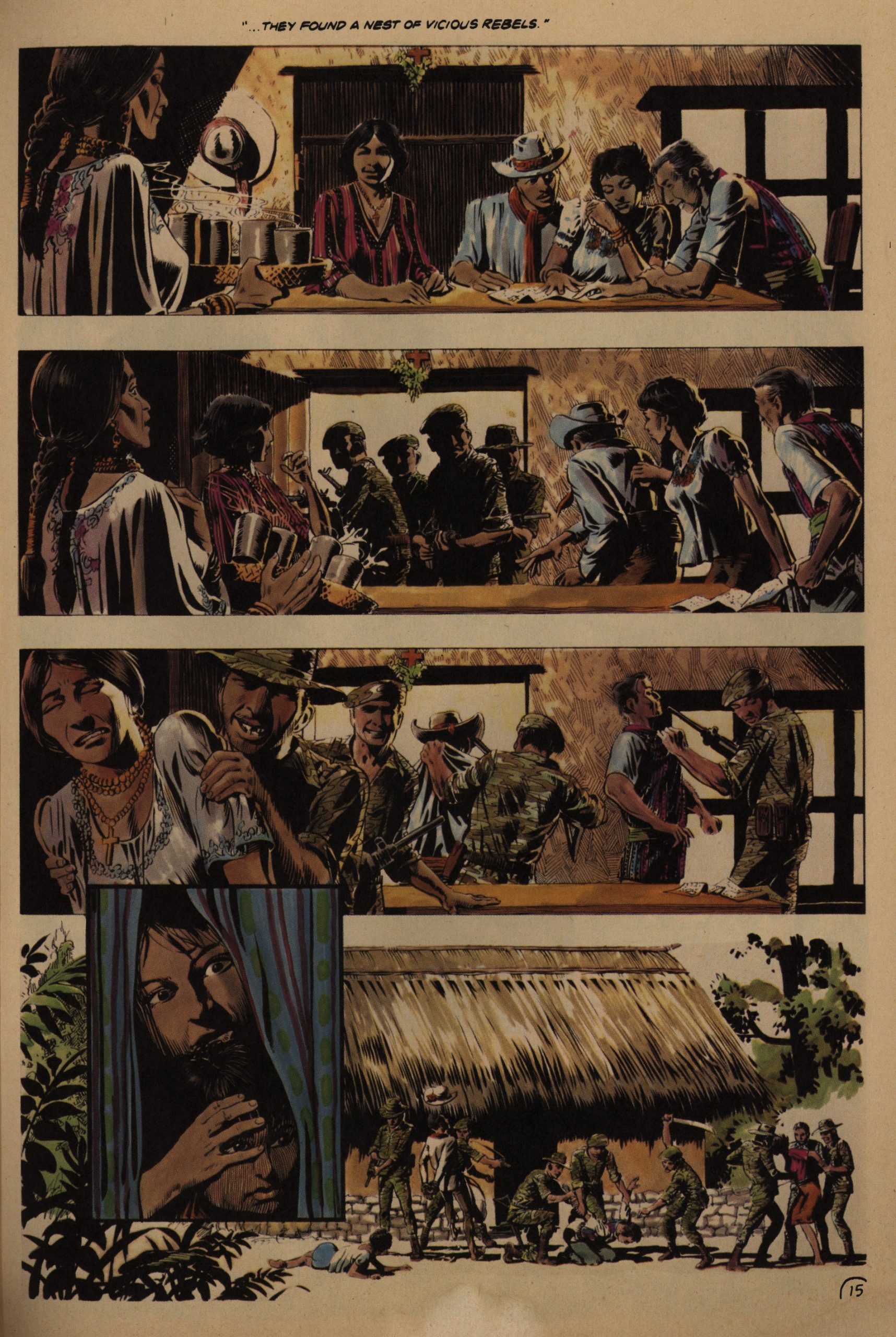

Which doesn’t start off in the most pleasant way, either: A transsexual man kills a drag queen with a razor blade. (And is then immediately killed by Our Hero.)

And just… how… was Mayerik doing the colouring? Crayons? I understand that they didn’t want to do mechanical seps on an “adult” comic like this, but this is just insane.

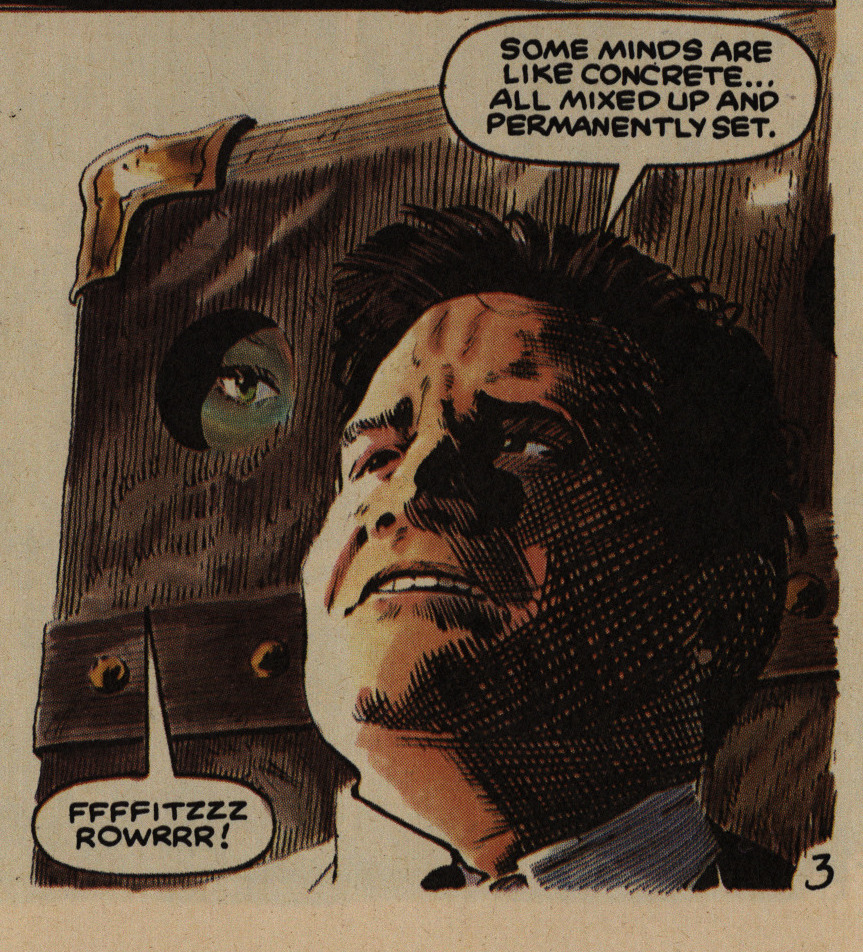

It’s also got some surprising amateurish problems like inconsistent word balloon placement, making the reader guess what order to read stuff in.

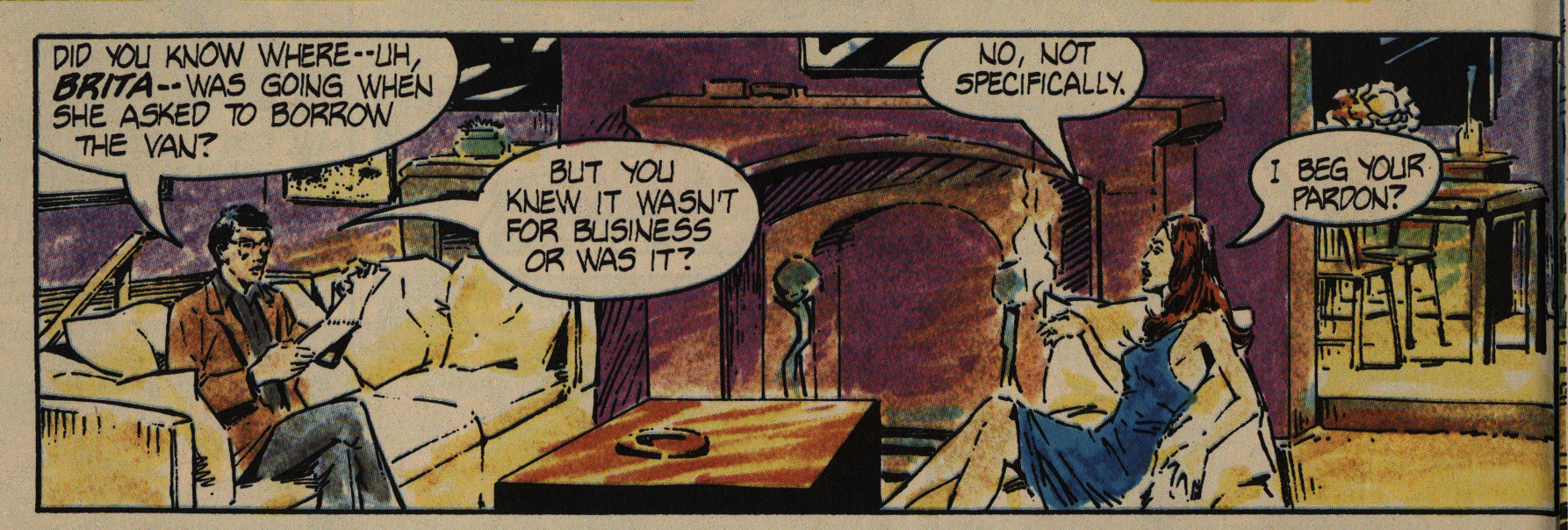

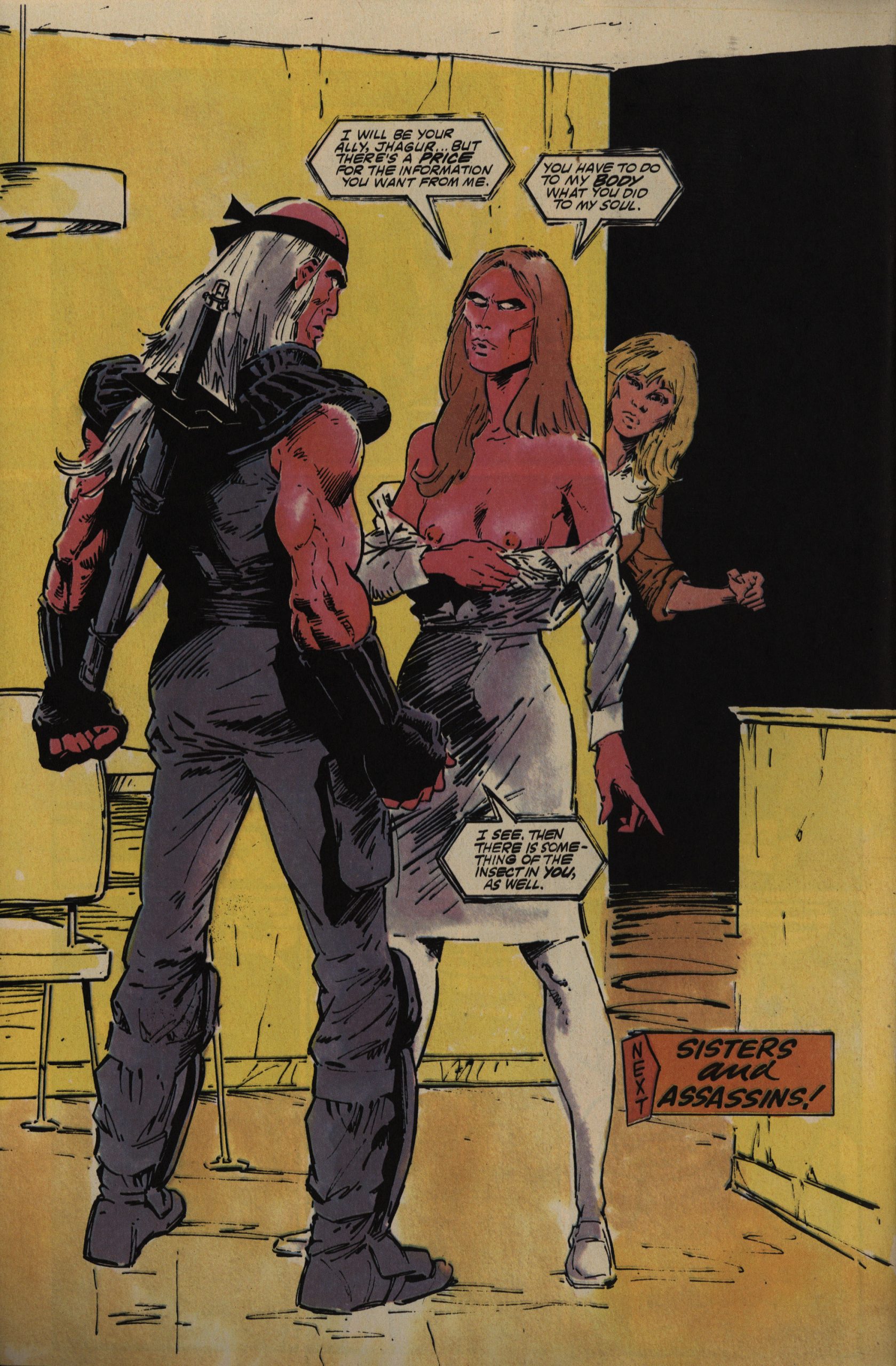

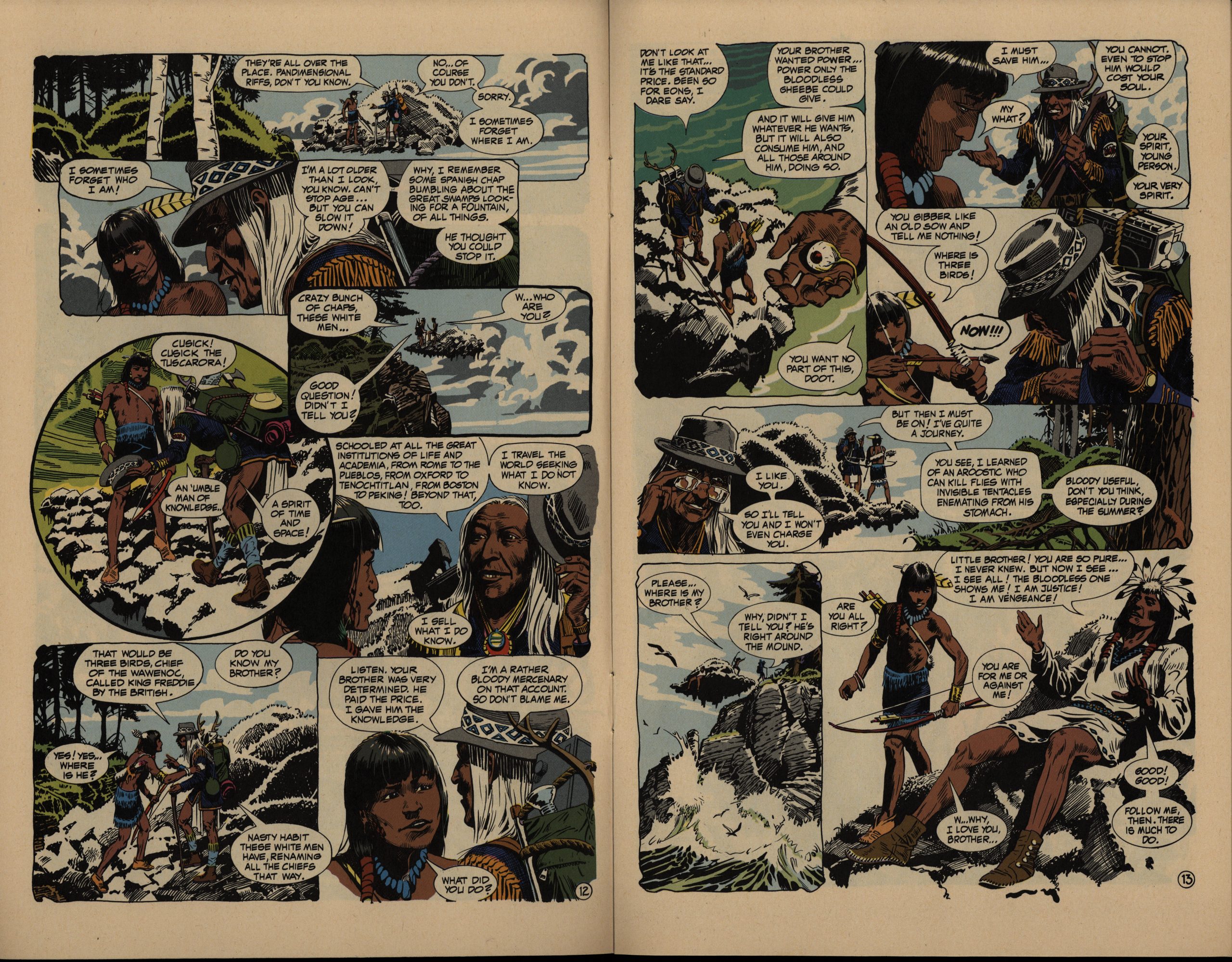

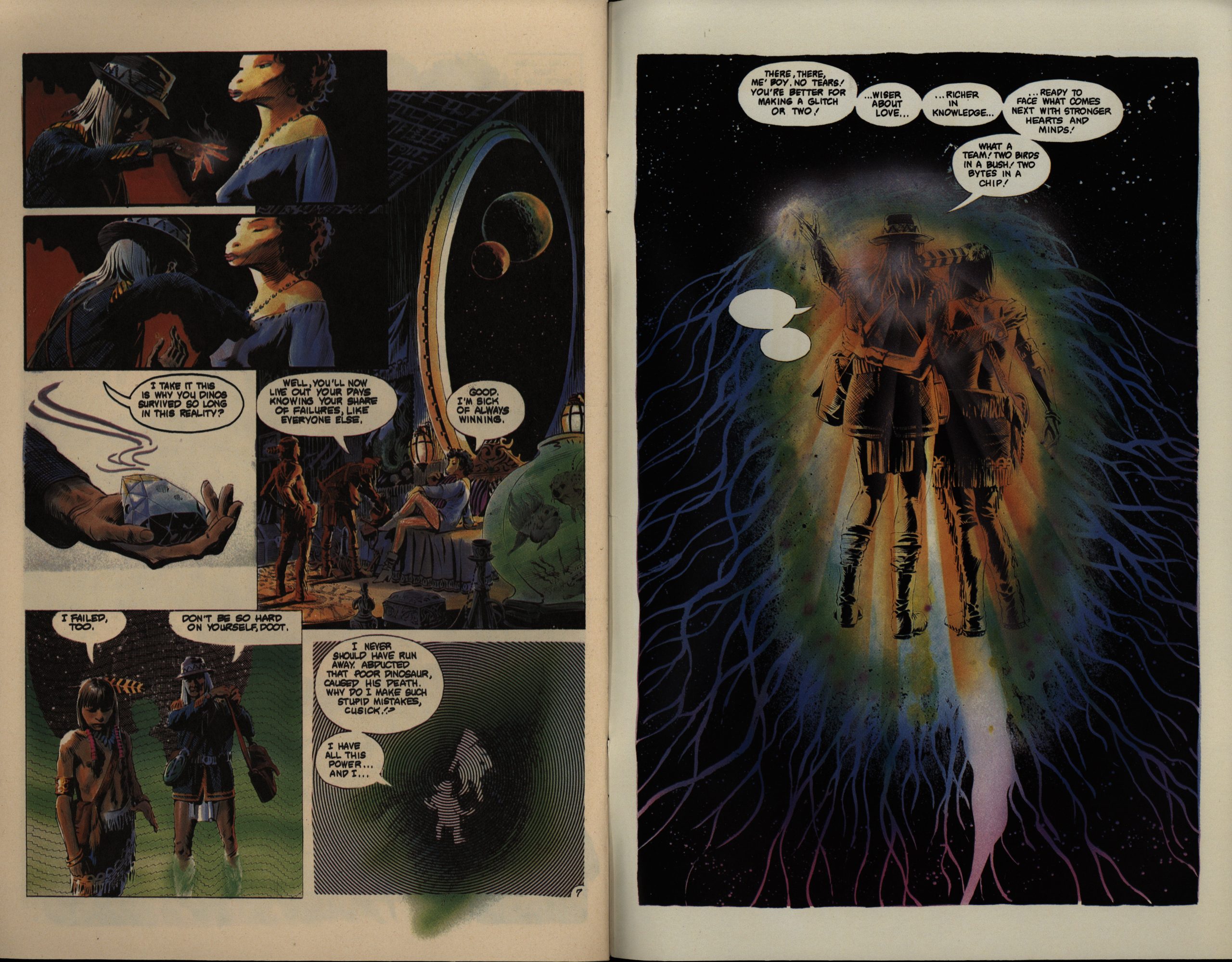

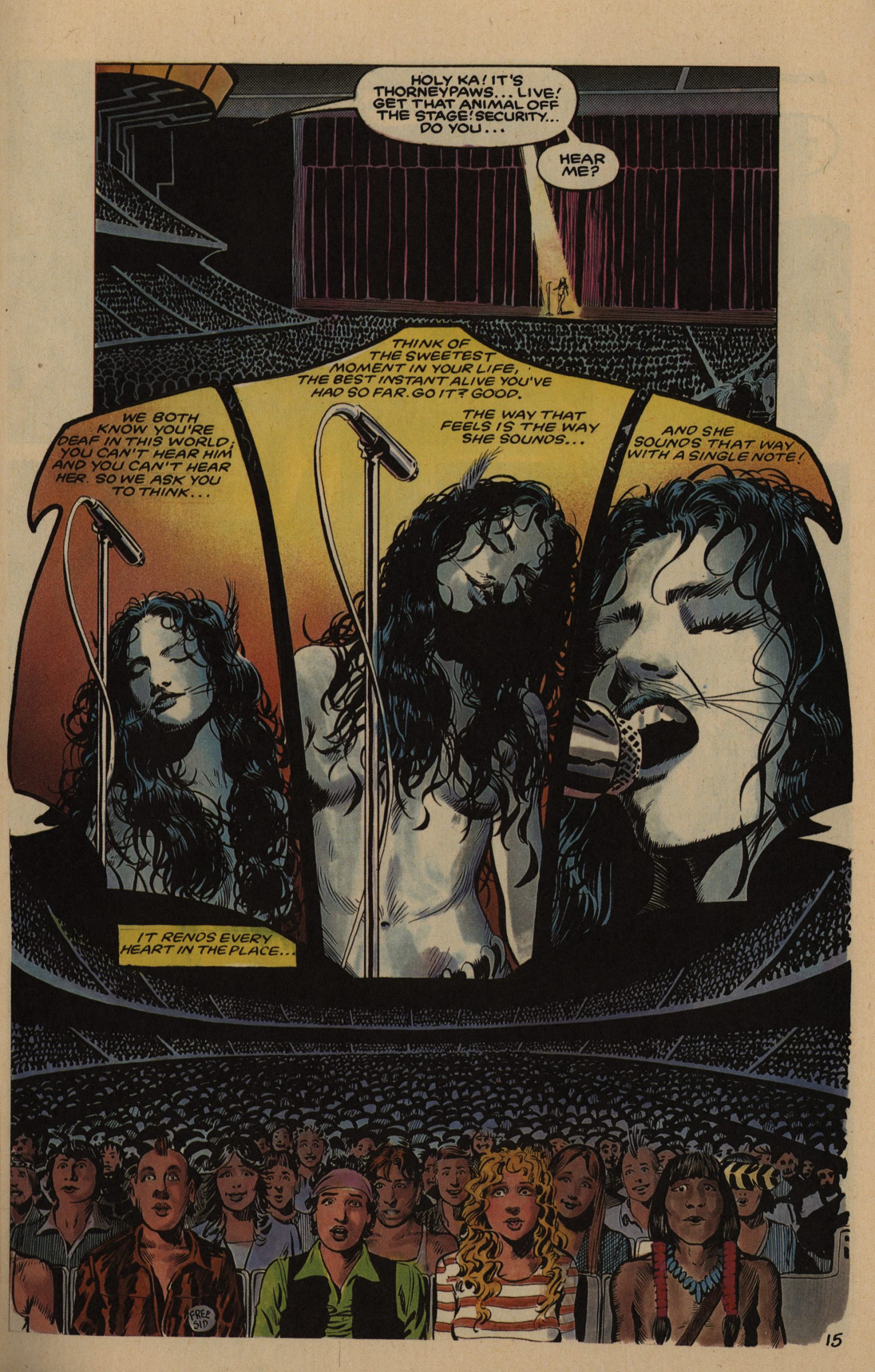

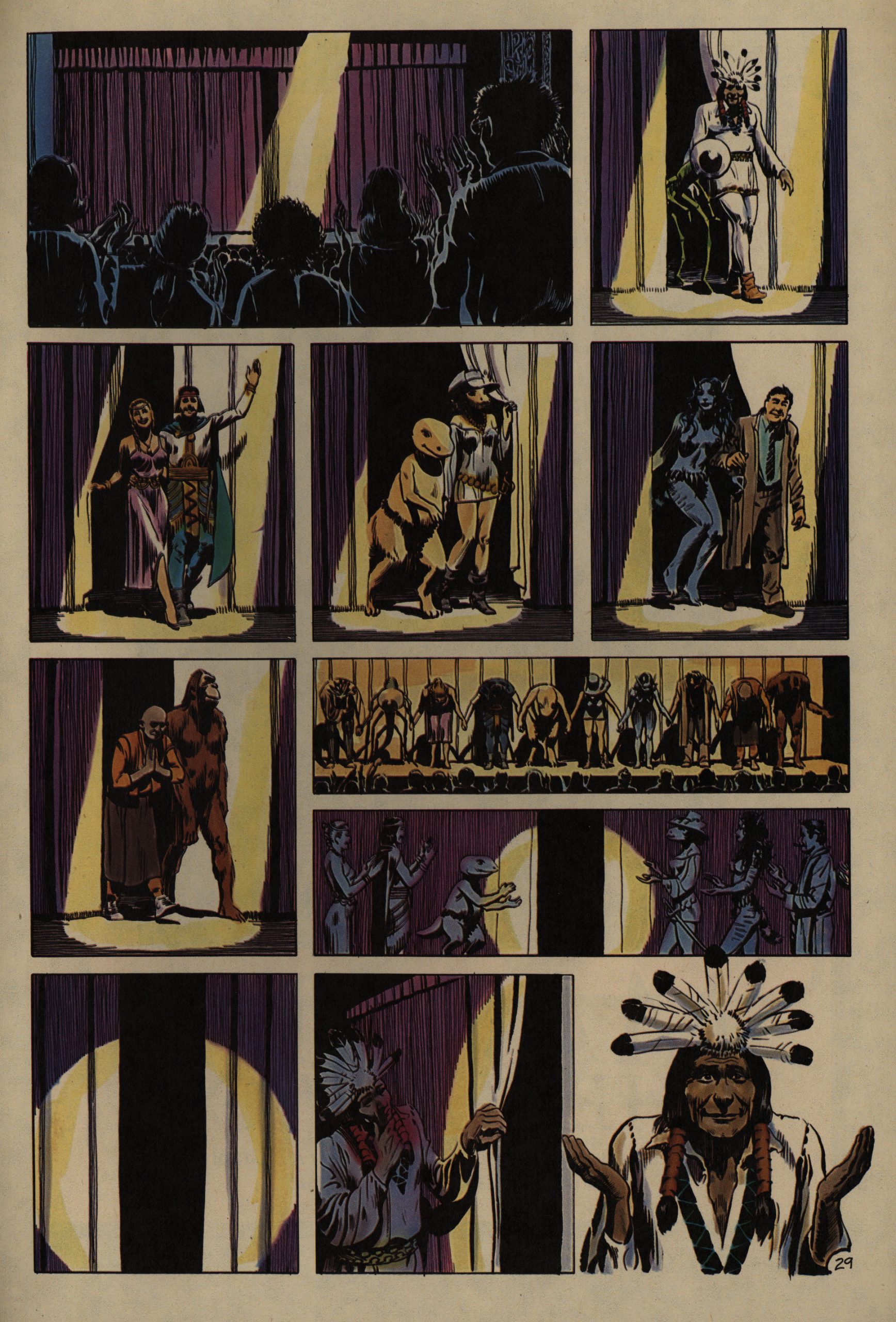

That said: This is a pretty interesting story and milieu we’re getting. There’s a bewildering number of characters, but they all do seem like distinct characters, both in the way they talk and the way Mayerik depicts them. The story, which seemed like a really simple torture/revenge story in the graphic “novel” now grows satisfyingly complex, with all these characters having their own motives, and have agency beyond being bit players to the hero with thinning hair.

Gerber apparently quotes from a book about popular culture, which I first took at face value, and as a defence against detractors saying that the book is way, way too violent.

But as becomes clearer later in the issue, the book in question is written by one of the characters in the book (or somebody with connection to these characters; I’m not completely sure).

I’m a sucker for post-modern tomfoolery with authorship, so I’m totally on board with this. My branes went “oo fun” when I got to this page.

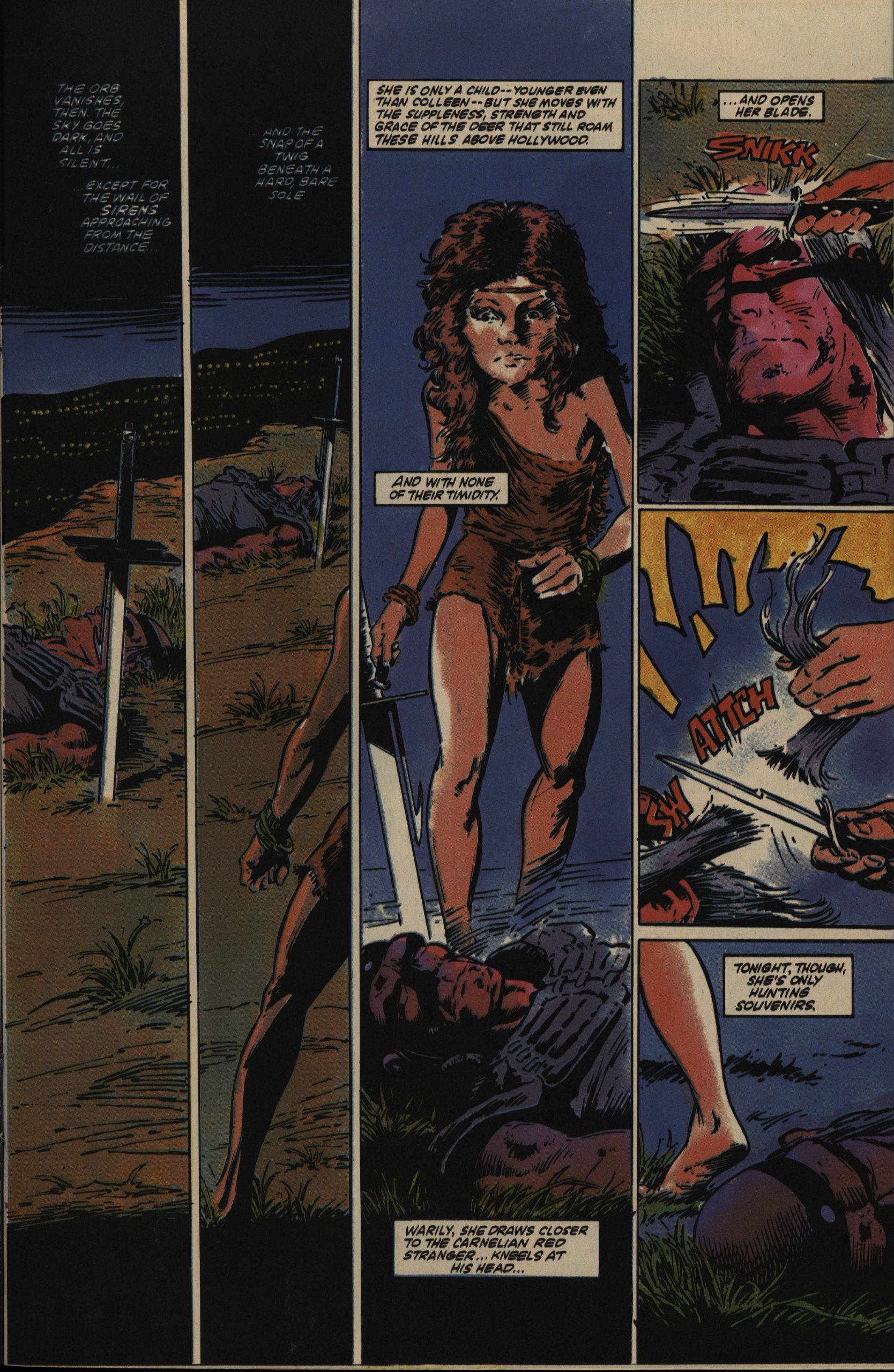

Gerber is just all kinds of clever with how he keeps things interesting. This is how a character that seems like would going to become (oh, the tenses) important to the story later is introduced. Yes, Mayerik isn’t quite up to actually depicting a child, so it looks like a woman with a bizarrely big head, but beyond that, it’s all kinds of good.

And then… the book was cancelled.

writes in The Comics Journal #95, page 11

Marvel axes Void Indigo after 2 issues:

lateness, controversial content cited

Epic Comic’s controversial new

Void Indigo series is being

cancelled with its second issue,

making it the first ongoing Epic

series to be cancelled. Only two

months earlier, a copy of the

graphic novel had been seized by

Canadian customs officials who

thought it might have violated

pornography statutes.

Dealer resistance and schedules:

According to Void Indigo’s

creator and writer, the main

reason the series was cancelled

was dealer resistance to its

unusually violent and bizarre

concepts. and attendant low

sales. According to Gerber, sales

were in the 30,000-40,000 range.

Secondarily, he said, he was late

on the book, having only a

rough outline for the first half-

dozen issues.

Gerber said that prior to the

cancellation, he and Epic Editor

Archie Goodwin discussed

changing the book’s premise to

make it more palatable to the

audience, but Gerber didn’t

think it would avail anything.

“The book’s image was already

fixed in everyone’s minds, and I

wasn’t interested in watering

down the book’s concept—it

wouldn’t win anybody over, and

it would only alienate the iwo or

three people who liked the

book. ”

Marvel also said that Gerber

was behind schedule on the

book, and that the sales on it

were harmed by this. Steve

Saffel, Marvel’s assistant

promotional manager for direct

sales, said that Gerber’s work

on projects such as Marvel

Productions (Marvel’s

animation studio) made it

difficult for him to maintain a

regular schedule on Void

Indigo. “Irregular shipping

schedules hurt our books

badly,” he added. Saffel said

that the creative members

involved “scrambled about” for

a while, but eventually there was

no choice but to cancel the

comic.

Seized in Canada: During its

brief life span, the comic set a

precedent for Marvel, as it was

seized at the Canadian border

by customs officials who

thought the comic might have

violated pornography statutes

regarding the depiction of

women.[…]

After the initial problems he

had with the graphic novel, Van

Leeuwen made the decision not

io carry the regular Epic series

at all. assuming the Series would

, continue on in the same vein.

just took a moral stand, and

-none of the stores I supply will

carry it from me,” he said. ‘ ‘My

accounts can go elsewhere if

they want them. I personally

object to the book.” Prior to

Marvel’s decision to cancel the

series, Van Leeuwen expressed

his feelings 9bout the book.

“I’d just like to see Marvel cut

off the whole series, to tell you

the truth,” he said.

No returns: Van Leeuwen

expressed his displeasure at

Marvel’s refusal to allow returns

for credit on copies of Void

Indigo. According to Saffel, no

returns will be allowed, but Van

Leeuwen thinks they should.

“Marvel feels [retailers and

distributors] were sufficiently

warned about the book’s

contents, but they didn’t tell us

it was going to be grotesque,”

he said.

Art Cover writes in The Comics Journal #100, page 97

Steve Gerber’s comeback was stopped dead in

its tracks with the furor caused by Void

Indigo. However, as Gerber (last intervieued

in Journals and 957) displays in this litter•

view, this setback will not dismay him. For the

first time since before his lawsuit against

Marvel in 1978, Gerber plans to write the

character that first propelled him to fandom’s

spotlight—Howard the Duck. While he is not

entirely certain that the book will actually

appear, and while he is equally unsure about

its reception in a marketplace that is more con-

servative than the one he terote for in ’78,

Gerber is going to ask America to ‘ ‘get down ‘

once agatn.

This interview was conducted by Art Cover„

transcribed by Mark Thompson and Tom

Heintjes, and was edited by Gerber and

Heintjes.

ART COVER: I’d like to start off by talking

about Void Indigo.

STEVE GERBER: Naturally. (laughter]

COVER: though 1 sure that 1

liked the book, I felt that it wasn’t given much

of a chance in the marketplace, to succeed or

fail on its own merits. What happened?

GERBER: Well, most of the reporting

about it has been fairly accurate. Maybe

too much was made about the incident of

the graphic novel having been stopped at

the Canadian border. Essentially What

happened was, a box of books broke open

at customs, Someone looked at the book,

was disturbed by the contents, and sent

one copy on to Ottawa for review by

Canada’s censorship board. The other 199

copies in the box went on to whatever

dealer ordered them. Nothing more ever

came of it.

But there were a number of problems sur

rounding this book. Certain distributors

themselves, personally, found it objec-

tionable. Some dealers objected to the

language, the nudity, the violence. One

distributor even mounted a campaign to

discourage his retailers from ordering the

Ex»oü.

COVER: Do sou u.’ant to sas who that was?

GERBER: NO, because can’t substan-

tiate it. I’m only relating to you what other

people have told me about this.

The book made an excellent target for

certain people who are disturbed about the

current state of comics. It was violent, the

language was rough, there was not a clearly

sympathetic heroic character at the fore of

the series—although I don’t think Jhagur,

the protagonist, was unsympathetic, either

—just extremely strange.

COVER: Neutral.

GERBER: Ambiguous, yeah, and difficult

to relate to. Also Void Indigo was a book in

its infancy, an easy book to mount a cam-

paign against. And a book that would be

easy to get canceled. I think a lot of people

took out a lot of frustrations on it. Also, I

think some people just genuinely didn’t

like it. Maybe most people didn’t.

Anyway, to wrap this up, the dealers

didn’t want to order the book, the

distributors didn’t want to carry it, and,

under those circumstances, Marvel didn’t

want to publish it, because it wasn’t going

to make any money. My feeling was, rather

than change the book and bring it more in

line with the mainstream, let it die a quick

and painless death. Archie Goodwin and

Val Mayerik agreed with me completely.

We never fought the cancellation.

COVER: Do you think it might have been a

capegoat, reflecting some people’s frustration

with Marvel? That they simply picked on

Void Indigo, a book they didn’t understand,

using it as a uay of saying, “‘Watch what you

put out!’ Not necessarily because of the sex

. and the violence, but because there’s just an

easy’ target.

GÉRBER: The sex and violence made it

an easy target. But what you’re suggesting

may be true to some extent. I wouldn’t

want to minimize, though, the degree to

which some people just didn’t care for it or

were offended by it.

COVER: Well, I talked to some who were

offended, and I talked to some who liked it.

GERBER: You found someone? (laughter)

COVER: Yes, 1 did! Really, absolutely.

GERBER: Who? Tell me!

COVER: One of the bookstore’s employees

always liked the book. But she wasn ‘t a regular

annics reader. She just reads alternative stuff.

GERBER: Most of the people I know who

liked it—and believe me, I can count them

on the fingers of both hands—were not

regular comics readers. A lot of them were

very impressed with it and didn’t under.

stand the reaction to it. But then, these are

people who go to movies regularly, who

read contemporary fiction..

COVER: Who are interested in the sex and

tiolence in their own lives.

GERBER: Exactly. [laughter) I couldn’t

have put it better.

I had forgotten about the boycott stuff, and I had suppressed this bit:

COVER: I understand Void Indigo was

originally a version of Hawkman that yu tried

to do for DC.

GERBER:- Yes, that is true.

COVER: And when I saw the final Product; I

just couldn •t understand. How many changes

did take it through?

GERBER: Many. Obviously, if there had

been any resemblance left to Hawkman by

the time it was sold as Void Indigo, we

would have been in big trouble.

It started out as a revamping of Hawk*

man, combining the Earth-I and Earth•2

versions into a new version of the charac-

ter. The idea being that he was an alien

from Thanagar who was the reincarnation

of an ancient Egyptian prince. That basic

idea survived into Void Indigo. All the

names were changed, of course, the wings

disappeared, the powers were completely

different.

But what did the critics think?

Carter Scholz writes in The Comics Journal #98, page 43

A lot of page space is given to details of

torture and death. There is, as in The

Medusa Chain, as in the films of Brian

DePalma, that “waning of affect” Jameson

mentions as a trait •of the post-modern.

And again, the craft WOFk is high, and the

guesomeness is justified in terms of the

story—but it is given that same peculiar

emphasis.

Says the alien: “Your agony—and that of

those Of your disciples—will provide the

entertainment from now on.”

Unquestionably the details of mass death

are in our contemporary air. And no one

can honestly deny Gerber’s or Colon’s

right to display them in a coherent story.

But we may, with . all critical distance

abolished, ask why. To what end? Enver-

tainment? Some of this stuff would gag a

maggot:[…]

Gerber is engaged in something quite

complicated here. We hear a lot about

expanding the potential of the comics

medium, but usually from the standpoint

of visual innovation. Gerber, seemingly,

-could not care less about the visual, and is

bent on telling, in a comi% a kind of story

inimical to comics.

Steve Gerber writes in The Comics Journal #99, page 8

In the future, Groth, will you kindly

check out your suppositions before

presenting them as facts! Please?

Void Indigo was, in fact. offered to

Eclipse, First. Pacific, and DC, as well as

Mar v el.

All of the independents passed: Eclipse

it too violent; Pacific couldn’t

visualize how the prose treatment and

Val Mayerik’s presentation drawin$

would translate into a comic book; First

claimed it had a similar project in the

works. DC was lukewarm toward Val’s

“Ork and declined to negotiate on

ownership of the copyright and division

of ancillary income; that left us with

nothing to discuss.

We chose Epic for three reasons:

In a market dominated by mutant nin•

ja teenagers, we felt this book needed

every ounce and, yes, every dollar of pro-

I-notional Support it could get. Marvel.

we knew, was capable of providing that

support; we were less certain about the

smaller publishers.

Secondly, both Val and I like working

with Archie Goodwin, Who, by anyone’s

standards, is one Of the most competent

and creative editors in the industry.

Thirdly, following the out-of-court

settlement of the Howard the Duck case,

it struck me that it would make an inte-

resting Stateinent to return to Marvel

with a property copyrighted in my name

(and Val’s, of course).

R Fiore writes in The Comics Journal #96, page 34

There’s screwy and then there’s screury.

“Humans… cannot bear to face the dark-

ness in their nature” in these nasty old lat-

ter days (according to the introduction)

but if Steve Gerber has his way you’ll get

your minimum daily requirement and then

some. Three bloody killings in this issue

and it feels like more. Gerber’s been on this

graphic violence kick for a good five years

now, and he still hasn’t figured out that the

true darkness is inside the human heart

and not in the act of cutting it out.

RA Jones writes in Amazing Heroes #58, page 58

AVOID INDIGO

“He is gashed, punctured, ham-

mered, and mauled.”

By the time you reach the mid.

way point of this graphic novel,

you may feel equally tortured. Void

Indigo is unquestionably one of the

most vividly violent books of the

year. Blood flows as freely as

water, as the characters are

maimed, mutilated, and murdered.

[…]The most discussed aspect of this

book will probably be the graphic

aviolence, but quite frankly it made

little impression on me one •„vay or

the other.[…]

The art is atrocious, far below the

level at which Val Mayerik is

capable of working. It looks as if he

used fingerpaints to execute the

graphics. If he intended to do the

coloring, he •would have been wise

to purchase a dictionary first. Then

he could have looked up the word

“indigo” and learned that it

describes a dark blue color—not

the sickly yellow he employs on

more than one occasion. The hues

throughout the book look pale and

watered down, especially when

compared to the vibrant coloring

evident on the front and back

covers.